The historic, widely publicized race through Alaska’s snowy wilderness was designed to deliver antitoxins that would save children from dying of diphtheria. The race lasted five days, during which twenty dog sled teams—comprising both people and dogs—made exchanges along the route. Thanks to their efforts, many sick children were saved.

Advertisement

At the end of December 1924, an epidemic of diphtheria broke out in the town of Nome, Alaska. Curtis Welch, the town’s doctor, who ran the local hospital alongside four nurses, diagnosed the disease as diphtheria only on January 24, 1925, after several children had already succumbed to it.

Diphtheria is a highly contagious bacterial disease that, thanks to its vaccine, has almost been forgotten today. Following infection, the diphtheria bacteria colonize the epithelial cells of the throat, causing pharyngitis (sore throat, fever, and cough) along with shortness of breath, bloody nasal discharge, and the formation of a membrane in the throat that can block the airways. The tonsils and lymph nodes in the neck swell, and the bacterial toxins disrupt heart muscle cells and cells of the nervous system. This lethal combination led to the deaths of many children, most of them under the age of five.

Sled driver Leonard Spale with six dogs, with the dog Togo on the left | Carrie McLain Museum / AlaskaStock

Nowadays diphtheria is extremely rare due to the vaccine, containing an inactivated toxin (toxoid) of diphtheria bacteria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae), which was introduced into childhood vaccination schedules in the 1930s. The race took place before this time, and therefore, at the time, sick patients received an infusion of serum from horses that had previously been injected with the toxin. Serum is a clear yellowish fluid separated from blood and blood cells, containing various proteins including antibodies. Injecting the toxin into a horse causes it to produce antibodies against the toxin. When serum derived from a horse is administered to sick children, its antibodies recognize and neutralize the toxin in their bodies, thus saving many lives.

In Nome, antibody preparations that were six years old had expired. A shipment of new antibodies, ordered several months earlier, was slow to arrive—exacerbated by Alaska’s harsh winter weather, which had closed the port and its surrounding area due to ice.

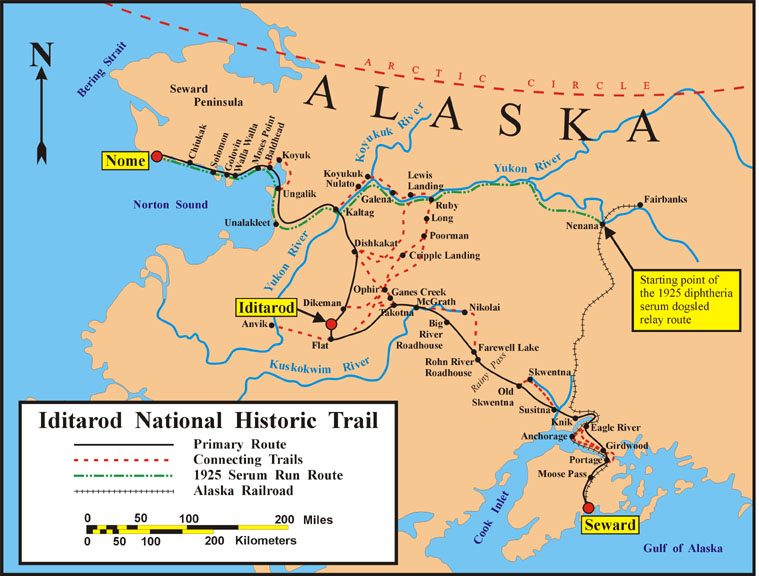

Welch sent an urgent telegram to the authorities, and on January 28 a new shipment of antibody preparations departed from the hospital in Anchorage by train to the town of Nenana, about 1,350 kilometers from Nome. From there, the shipment was transported by dog sleds through temperatures lower than 40 degrees below zero, all while ensuring that the antibody preparations did not freeze and thereby lose their effectiveness.

The Great Race of Mercy routes in 1925 (green) and today | U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Public Domain

Thus began the Great Race of Mercy, also known as the Serum Run. The sled teams and their dogs were rotated at twenty stations along the route. The shipment reached Nome after five and a half days, on February 2. Unfortunately, some of the dogs did not survive the journey and some of the drivers suffered from frostbite, but nonetheless the antitoxin preparations managed to save a significant number of children. The journey was broadcast in real time by the media of the time—radio, which was then quite new, and newspapers. Two of the lead dogs—Togo and Balto—were featured in the coverage, and Balto’s statue still stands today in New York City’s Central Park.

In March 1973, an annual tradition began to recreate parts of the Great Race, and since then every March the great Iditarod dog sled race starts in Iditarod (not Nenana), covering 1,800 kilometers of ice and frozen lakes all the way to Nome.

In 2019, the film Togo was released in theaters, bringing this fascinating story to life.

Hebrew editing: Galia Halevy-Sadeh

English editing: Elee Shimshoni

References: