An eight‐month‐old toddler was hospitalized at Ichilov Hospital suffering from pneumonia and was diagnosed with Legionnaires’ disease. She inhaled the causative agents—Legionella pneumophila bacteria—via steam from a humidifier operating in her room to ease her breathing.

Advertisement

In July 1976, reports began to accumulate from various hospitals across the United States regarding an outbreak of severe pneumonia, whose main symptoms were chills, high fever, chest pain, and severe delirium. In total, 182 people fell ill within one month, and 29 of them died. The epidemiological investigation revealed that all the patients had either attended a convention of the American Legion at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia or had stayed at the hotel during the convention. The symptoms appeared about a week after the event ended. Following the incident, the hotel was closed for several months. The then-unidentified disease was named Legionnaires’ disease—a name that remains to this day.

Six months later, in January 1977 (48 years ago), researchers at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta, led by Joseph MacDade, succeeded in isolating bacteria from the lungs of four victims, cultivating them in the laboratory, and proving that they were the cause of the disease. The bacteria were named Legionella pneumophila—after the disease and its primary symptom, pneumonia. The bacteria were also found in the water of the hotel’s cooling tower, and it was determined that they were spread throughout the hotel via the air conditioning system. It was then recalled that in 1974 a large conference (with over 1,000 attendees) was held at the same hotel, during which twenty individuals fell ill with an unidentified disease, and two of them died.

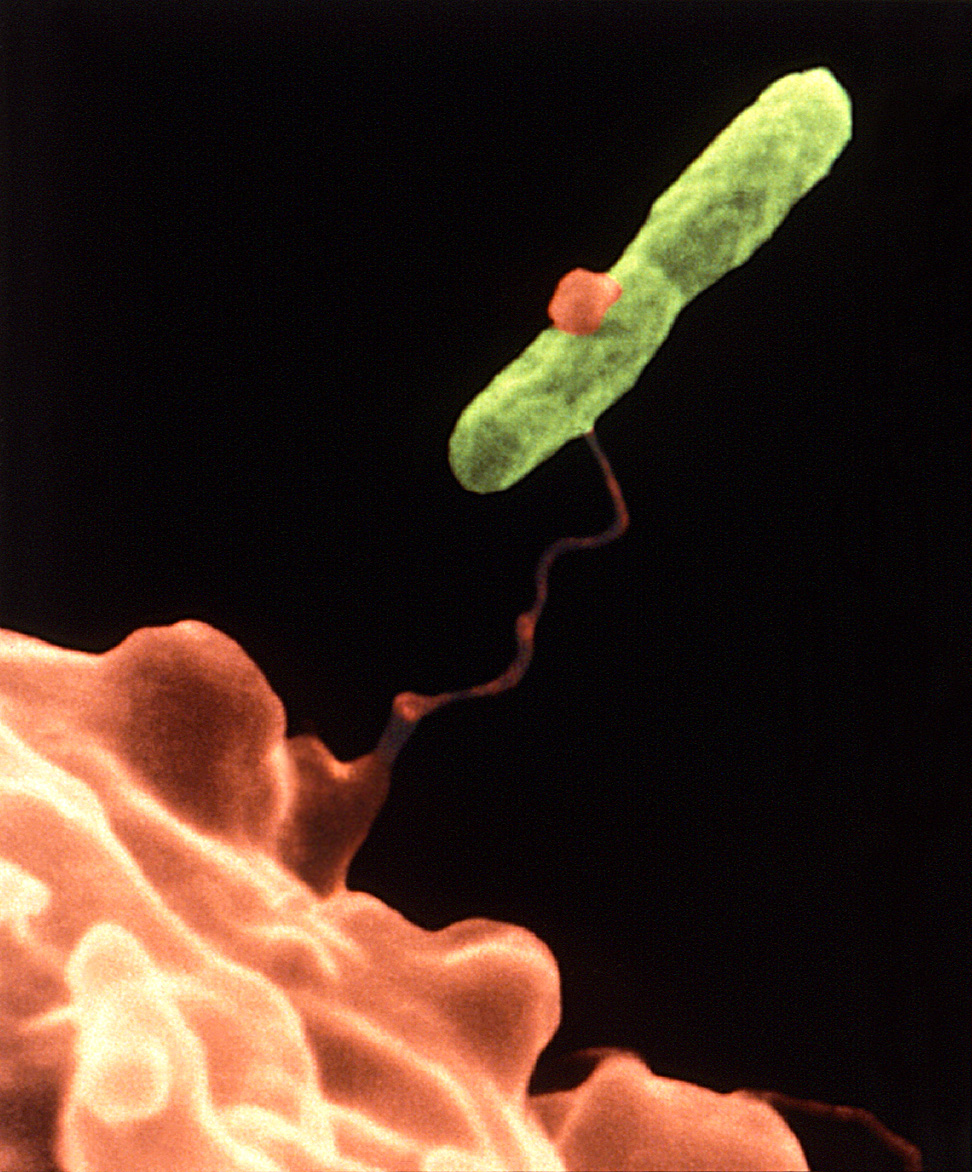

Scanning electron micrograph of Legionella pneumophila. Source: CDC/Janice Haney Carr

When the researchers later returned and examined samples from past patients that had been stored in freezers, they retrospectively discovered additional outbreaks of the disease, the earliest of which occurred in 1943. The largest outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease occurred in February 1999 at a flower exhibition in Bovenkarspel in the Netherlands, which was attended by approximately 77,000 people. Hundreds were hospitalized, 32 did not survive, and 206 were in critical condition. The bacteria were detected in two hot tubs and in a cold water dispenser. Proper water chlorination according to regulations could have prevented the outbreak.

Back to the present: In January 2025, an eight‐month‐old infant was hospitalized in critical condition at Ichilov Hospital after contracting Legionnaires’ disease [1]. She inhaled the bacteria causing the disease from a home humidifier that was operating in her room to ease her breathing. The bacteria multiplied in the device’s water, and contaminated spray droplets entered the infant’s lungs. We wish her good health.

It should be noted that the Ministry of Health recommends avoiding the use of home humidifiers. This is because their medical benefit in alleviating winter illness symptoms is minimal, and as we have observed, they pose a risk of disease. This is also the stance of the Israeli Association of Family Medicine, which published a white paper in 2012 following five similar cases [2].

Since their discovery, Legionella bacteria have been extensively studied and their natural habitat has been identified. They are found in low concentrations in any wet or damp environment—lakes, pools, rivers, and streams—but not in salt water. They have been detected in the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park (at 63°C), in cold lakes in the Alps (at 10°C), and even in water at near freezing temperatures. In 1979, following the eruption of Mount St. Helens in the United States, Legionella were also found in water reservoirs that were formed following the eruption. The bacteria are also present in various types of damp soil, as well as in many man-made damp facilities: cooling towers, cooling cells, faucets, sprinklers, ice and ice cream machines, fountains, dental equipment, hot tubs, and drinking fountains—each of which provides a suitable habitat for the bacteria to thrive.

In water, the bacteria may be found free, residing within amoebae cells (where they replicate), or on biofilms of cyanobacteria. They replicate exclusively within cells and are therefore considered intracellular parasites. In humans, they replicate within macrophages—phagocytic cells of the immune system.

Scanning electron micrograph of Legionella pneumophila adhering to a pseudopod of the amoeba Hartmannella vermiformis. After attachment, the bacterium invades the amoeba and replicates within it. Source: CDC/ Dr. Barry S. Fields

Legionnaires’ disease [3, 4] is a secondary disease, meaning that young, healthy individuals do not typically fall ill. It may affect infants, the elderly, and those with compromised health, such as individuals with weakened immune systems, patients undergoing chemotherapy, and those with chronic lung diseases. It should be noted that prolonged smoking and heavy alcohol consumption impair the immune system’s function.

People outside of the high-risk groups can be infected with Legionella (L. pneumophila and other species), but they tend to develop Pontiac fever (named after the city in Michigan where it was discovered in 1968), a milder, flu-like illness that is not life-threatening and resolves on its own within a few days.

Legionnaires’ disease is one of the hospital-acquired infections and is common among organ transplant recipients and dialysis patients. Most patients become infected by inhaling droplets of fluid from air conditioners or other water sources, and even from inhalation of dust particles containing the bacteria. Following an incubation period, lasting between two and ten days, severe pneumonia develops.

The disease can be treated with antibiotics, yet some patients do not survive. The earlier the treatment is administered, the higher the chances of survival [5]. Some survivors suffer prolonged complications. The patients do not endanger those around them, and there are no reports of direct patient-to-patient transmission. Currently, there are no vaccines against L. pneumophila, not even in development.

As mentioned, Legionella bacteria are very common in the environment, and the main sources of infection are contaminated water systems. Large clusters of cases are typically detected after a prolonged stay in a public venue with such contamination, such as hospitals, hotels, and cruise ships. Occasionally, infections also arise from a humidifier.

The most effective way to avoid infection with L. pneumophila bacteria is to disinfect and purify water sources and facilities and to maintain them properly. It is also recommended to avoid using humidifiers in children’s and infants’ rooms.

Hebrew Editing: Smadar Raban

English Editing: Elee Shimshoni

References:

- “8-Month-Old in Critical Condition After Contracting a Dangerous Bacterium” – Maytal Yasur, Beit-Or – Israel Hayom: January 11, 2025 (Hebrew)

- Position Paper by the Association of Family Physicians – 2012 (Hebrew)

- Information on Legionnaires’ Disease – CDC Website

- Information on Legionnaires’ Disease – Israel Ministry of Health Website (Hebrew)

- A Review on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Legionnaires’ Disease: Legionnaires’ Disease: Update on Diagnosis and Treatment

- For further details – Dror Bar-Nir, 2015 (Hebrew)