In 2010, a prestigious journal published a paper reporting the discovery of bacteria in a lake in California whose DNA contains arsenic instead of phosphorus. Recently, the journal’s editorial board retracted the paper, 15 years after it became clear that it was based on scientific negligence and a flawed inference process.

Advertisement

All known living organisms on Earth share a common biochemistry based on six chemical elements: carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, and phosphorus. These six elements are the principal components of the four molecular groups essential for life: carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. It is hard for us to imagine how life could exist without one or more of these elements, yet such life may be possible. For example, according to the theoretical framework of alternative biochemistry, living beings in which silicon (Si), the element located beneath carbon in the periodic table, replaces carbon (silicon-based life), might one day be discovered. Another example—already observed in nature—is the replacement of oxygen by sulfur. Sulfur is located directly below oxygen in the periodic table and does occasionally substitute for oxygen in certain biological functions, especially under oxygen-limited conditions.

Directly beneath phosphorus (P) in the periodic table lies arsenic (As), which is very similar to phosphorus in its chemical properties, particularly in the way it binds to other elements. For precisely this reason, arsenic is poisonous in the biological systems familiar to us. For instance, during cellular energy production—specifically the oxidative-phosphorylation stage of ATP (the cell’s “energy currency”) synthesis—substituting arsenic for phosphorus usually halts the process and leads to the cell’s rapid death. Nevertheless, given the similarity between arsenic and phosphorus, it is conceivable that under special conditions living organisms could exist in which arsenic replaces phosphorus.

That idea was the central theme of a NASA-funded study published by Felisa Wolfe-Simon and her colleagues, all senior researchers working at NASA’s research center. The 2010 paper [1] posed an intriguing research question: Can arsenic be incorporated into DNA in place of phosphorus? According to the authors, they had discovered in California’s Mono Lake—a hypersaline, arsenic-rich lake—bacteria of the genus Halomonas that not only tolerate the arsenic in their environment but also use it in place of phosphorus as a building block for nucleic acids. The paper appeared in the prestigious journal Science, accompanied by a major NASA press conference. It generated great excitement: here, seemingly, was proof that alternative biochemistry is not merely theoretical but actually exists. Recently, fifteen years after publication, the paper has been officially retracted, and the journal published the reasons for the retraction [2].

The researchers claimed they grew the bacteria (humorously nicknamed “GFAJ-1,” for “Give Felisa a Job”) with a radioactive isotope of arsenic (73As) in a growth medium entirely devoid of phosphorus. Under these conditions, if the bacteria could use arsenic instead of phosphorus, they should grow while incorporating arsenic into their nucleic acids. To confirm this, the authors extracted DNA from the bacteria, purified it, and found it to be radioactive. From this they concluded that the radioactive arsenic had been incorporated into the DNA, replacing phosphorus. In retrospect, however, there was in fact phosphorus in the medium, albeit at low concentration, and it was phosphorus—not arsenic—that was incorporated into the DNA. The radioactive arsenic merely adhered to the outside of the DNA rather than becoming part of its structure. Apparently the DNA purification was inadequate, creating the impression that arsenic was present. In other words, the authors’ far-reaching conclusion—that they had discovered a new life form—was based on poor scientific methodology.

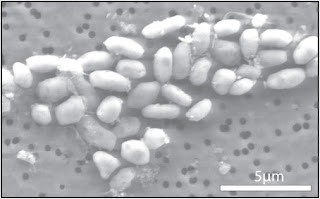

Halomonas bacteria under the microscope.

Photo: Jodi Switzer Blum, NASA

Since the paper’s publication, the scientific community has voiced extensive criticism—of the study’s quality, of its flawed interpretation, and of its very publication in a leading journal such as Science [3].

The phosphorus concentration in Mono Lake is five times higher than the arsenic concentration (88 milligrams per liter versus 17 milligrams per liter). In such a phosphorus-rich environment, there is no reason for bacteria to evolve the unique biochemical mechanism described by the authors. In other words, considering the characteristics of the bacteria’s habitat, the study’s foundational assumption was implausible from the start.

Two years later, in 2012, the same journal published two papers [4, 5] from other research groups showing that the Mono Lake bacteria are indeed arsenic-resistant, yet their genetic material contains phosphorus and not arsenic—just like that of all other bacteria. These papers thus refuted the original findings.

It is important to note that no one has claimed deliberate fraud by the authors, who still oppose the retraction of their paper. The prevailing view is that technical and scientific problems produced “flawed” data, which led to erroneous conclusions. The researchers were so enthusiastic about their surprising results that they failed to verify them thoroughly. Peer review, which should have identified the flaws and refused publication, also fell short. The retraction [2, 6] was issued only after 2019 guideline changes allowed a paper to be retracted for “flawed science,” and not only for intentional misconduct [7].

What about the responsibility of the prestigious journal itself, which failed in peer review and then delayed the retraction for many years? Was the lapse related to the paper’s NASA prestige? We may never know. What is certain is that every scientist involved in research must approach their own results and conclusions with skepticism, testing them by as many methods and from as many angles as possible, with proper documentation. The scientific method is not perfect, but the truth usually comes to light—sooner or later.

Main image: Mono Lake, California—tufa towers and high arsenic concentrations. Source: NASA

Hebrew editing: Smadar Raban

English editing: Elee Shimshoni

References:

[1] The original paper (now retracted) in Science

[3] Article on the original publication and ensuing controversy – Dror Bar-Nir, 2011 (Hebrew)

– Two papers that examined the same bacteria and contradicted the original study:

[4] Absence of Detectable Arsenate in DNA from Arsenate-Grown GFAJ-1 Cells

[5] GFAJ-1 Is an Arsenate-Resistant, Phosphate-Dependent Organism