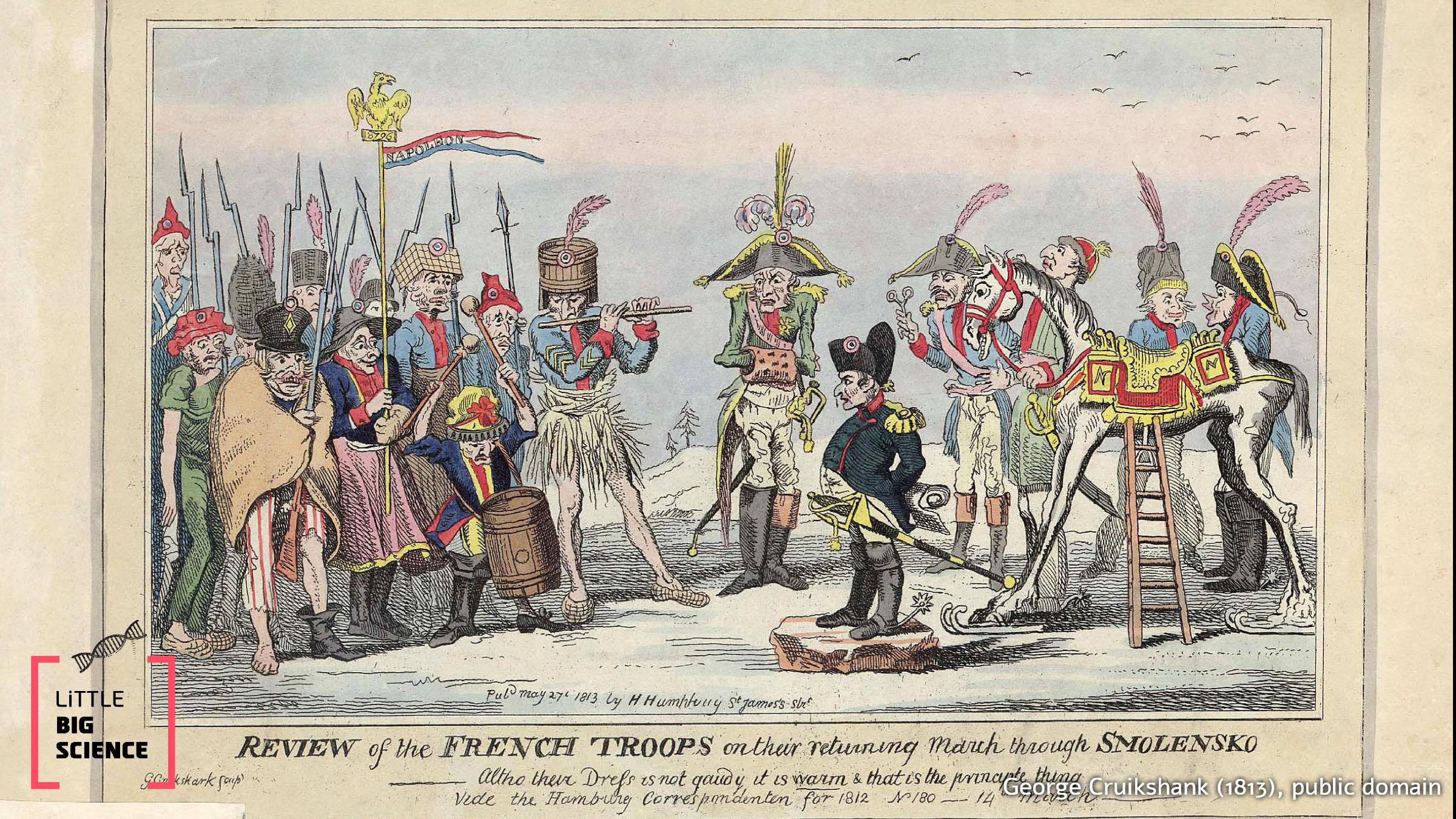

Hundreds of thousands of French soldiers from Napoleon’s army died in the winter of 1812 on the Russian steppes and were buried in mass graves. Most of them succumbed to infectious diseases, some of whose causes had already been identified. Recently, researchers managed to identify two additional pathogens—using PCR technology.

Advertisement

More than three hundred thousand soldiers from Napoleon’s army died in the winter of 1812 during the retreat from the Russian steppes, yet the Russian army had almost nothing to do with it—many of them succumbed to infectious diseases that spread among them. Over the years, researchers have attempted to identify the disease-causing agents (pathogens) that “helped” the Russian army halt the French invasion, and two additional culprits have now been identified.

Nicolás Rascovan of the Pasteur Institute, together with colleagues from Aix Marseille University in France and the University of Tartu in Estonia, searched for pathogenic bacterial DNA in the teeth of 13 French soldiers who fell ill and died that winter and were buried in a mass grave in Vilnius, Lithuania [1]. Bacteria do not survive in decomposed bodies, but traces of their DNA are preserved in bones or teeth because the bone mineral and the dentin in teeth protect them from complete degradation. Cold and dryness also aid preservation. The short DNA fragments that remain can be detected with PCR—a method sensitive even to minute amounts of genetic material. Of course, it is essential to prevent external contamination of the sample.

PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) technology has been in use for more than 30 years and became familiar to many of us during the COVID-19 pandemic. The method enables amplification of pre-defined DNA segments in a test tube, using the same “biological machine” that replicates DNA in living cells (e.g., before cell division)—the polymerase enzyme. Because the process takes place in a test tube rather than in a living cell, one must supply, in addition to the polymerase, the DNA building blocks (nucleotides) and two primers—short nucleotide sequences that mark the ends of the desired segment, one on each side.

In a process controlled by cyclic temperature changes, the polymerase repeatedly copies the desired segment: First, the two DNA strands are separated by heating; next, the tube is slowly cooled so the primers can bind to their complementary sequences on the molecule; finally, the tube is brought to a temperature that allows the polymerase to synthesize the segment. In each such cycle, lasting only a few minutes, the segment is duplicated. Thus, if we start with a single DNA molecule, after ten cycles there will be 1,024 identical molecules, and after twenty cycles—more than a million. The reaction will occur only if the tube contains DNA matching the sequence recognized by the primers. Once a sufficient amount of DNA has accumulated, it can be visualized by gel electrophoresis (a separation and staining method).

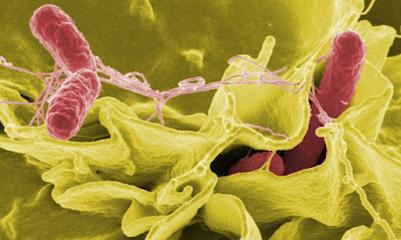

The researchers placed the DNA extracted from the soldiers’ teeth into PCR reactions that used primers specific to several suspected pathogenic bacteria. They detected DNA from only two of the tested bacteria: Salmonella (Salmonella enterica Paratyphi C)—a bacterium transmitted through contaminated water or food that cause paratyphoid fever, a severe intestinal disease; and Borrelia (Borrelia recurrentis)—a bacterium transmitted by body lice (Pediculus humanus corporis) that cause relapsing fever, a disease that emerged in crowded and unhygienic conditions following natural disasters or wars and has almost vanished with the disappearance of body lice.

Salmonella typhimurium bacteria (in red) attached to human cells in culture | Source: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, NIH

Dark-field microscope image of Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes. | Source: CDC image library

The teeth of those 13 soldiers did not contain the bacterium that cause epidemic typhus (Rickettsia prowazekii)—another lethal disease that breaks out under extremely crowded conditions, combined with poor hygiene, and that has accompanied many wars. Nor were the bacterium that cause trench fever (Bartonella quintana) detected—a disease best known from World War I [2]. Both bacteria were found in 2006 in a similar study that examined tooth remnants and louse remains from the graves of 35 other French soldiers at the same site [3].

Thus, two additional bacterial species have been added to the list of pathogens that “assisted” the Russian army, the cold, and the hunger in halting the French invasion. It is likely that further studies will reveal more pathogenic bacteria, and perhaps viruses as well. The agents responsible for dysentery, hepatitis, and pneumonia—diseases mentioned by medical historians describing the invasion—have not yet been identified.

PCR technology therefore helps decode, provide new information, or confirm existing knowledge about historical events. The current study adds on to previous research that has detected the genetic material of the Plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis, which was also found in medieval graves from the time of the first Black Death pandemic; and that of the bacterium that causes typhoid fever (Salmonella typhi), which also was also found in the graves of victims of the Plague of Athens (430 BCE). Likewise, in mummies and skeletons, scientists have identified the bacteria that cause tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, and Malta fever, as well as variola (smallpox) viruses, hepatitis B viruses, and malaria parasites.

Hebrew editing: Smadar Raban

English editing: Elee Shimshoni

References: