An international project in collaboration with the University of Haifa is attempting to decipher the language of whales using a new algorithm that differentiates the calls of individual animals. Perhaps soon we will be able to understand what the ocean’s quiet giants are saying to one another.

Advertisement

Deep beneath the ocean’s surface, almost beyond the reach of light, a language we do not understand is heard—not a language of words, but of sounds. These are short sound waves emitted by the internal sonar system in the heads of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus), and to the human ear they often sound like “clicks.” Sperm whales have the largest heads relative to body size on Earth: the head makes up almost one-third of their total length [1]. Inside this enormous head lies an organ filled with white fat called spermaceti. In the past, the white substance inside was thought to be sperm—hence the name—but it is actually a unique fat that, among other roles, acts as an acoustic lens that concentrates the sound waves that the whales receive. With these clicks the whales locate prey, navigate in the dark waters, and communicate with one another. Sperm whales can dive to depths of more than a kilometer, stay underwater for nearly an hour, and rely on sound to sense their surroundings. Their clicks travel great distances, spreading through the water, bouncing off the seafloor and the bodies of whales and other animals, creating a vast underwater communication network. Within this network real conversations take place [2]. Understanding these conversations means understanding how intelligent beings, different from us, perceive the world. If we can decode their language, we may catch a brief glimpse into complex non-human thought—and that may be one of the most intriguing challenges in modern science.

These questions led to the creation of Project CETI [3], an international initiative that includes Israeli researchers and seeks to decipher whale language using artificial intelligence. Before the communication system can be understood, however, one must first separate and identify the sound sources—no trivial task in an especially noisy sea. The ocean is far louder than we imagine: it hums with engine noise from marine vessels, with sounds from other communicating animals such as dolphins, and with echoes bouncing off countless stationary creatures (like sponges and corals) and from the seafloor—all blending into endless cacophony. The whales’ own clicks collide with one another, reflect off obstacles, and change in character depending on distance and water pressure. Even highly sensitive recording systems struggle to determine who produced each sound and where it came from. As part of the project, networks of underwater microphones have been deployed off the Caribbean island of Dominica, along with autonomous diving instruments, recording thousands of hours of whale communication. The decoding strategy begins with the understanding that each click emitted by a given whale propagates through the water as a sound wave. Part of the wave reaches the recorders directly, and part is reflected from the sea surface like an echo. Minute differences in arrival times between these waves—how long each one takes to reach the sensors and what the returning wave looks like—help scientists determine the direction and depth from which the sound originated. This is where the Israeli researchers come in.

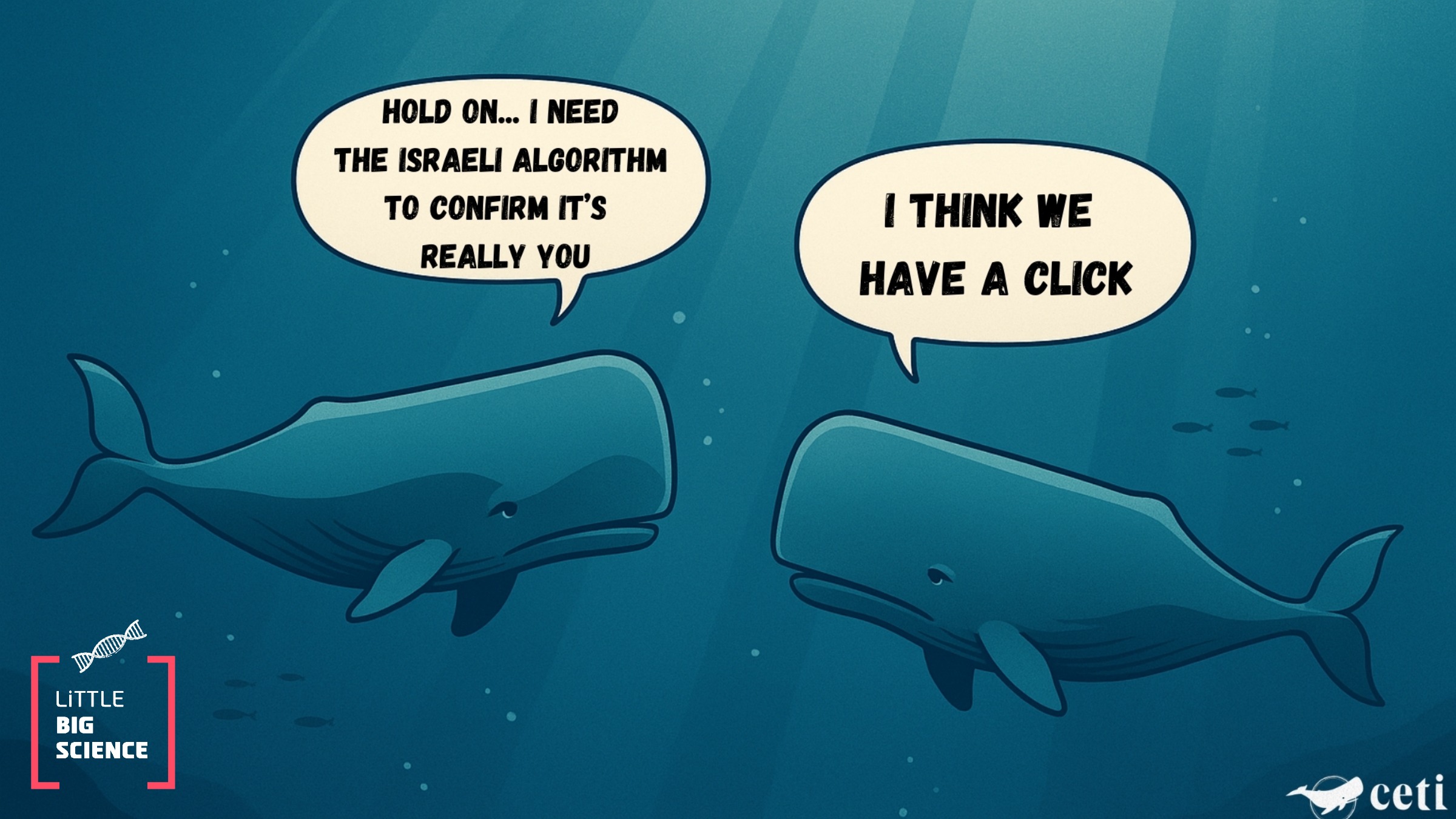

In the Underwater Acoustics and Navigation Laboratory of Prof. Roee Diamant, in collaboration with Prof. Dan Tchernov and the team at the Marine Research Station at Sdot-Yam of the Leon H. Charney School of Marine Sciences, University of Haifa, a new method has been developed that lets us “listen” to whales as never before. The algorithm they created factors in the travel time of each click to every microphone, the strength of its echo, and the path it took through the water column. Based on these tiny differences, the algorithm can identify which clicks belong to the same sound source—that is, to the same whale—even when several whales are speaking simultaneously. The algorithm does not truly “identify” individual whales; it does not know who is who. But it can separate the speakers: identifying clusters of clicks that behave consistently, with a unique spatial and temporal signature, and pointing out that they all belong to the same underwater “speaker.” Simply put, it brings order to a particularly noisy party: it knows who spoke at every moment, even when everyone is talking at once [4].

The study, published in a leading artificial-intelligence journal, offers for the first time precise tools for tracking sound sources and brings science a step closer to understanding whale communication, which may conceal a structure far more complex than we thought. Who knows? One day we may discover that these clicks are arranged according to an underwater “alphabet,” perhaps even in a rudimentary grammar, or something different altogether. It is not a language in the human sense, but it is certainly a rich, complex, and social communication system. Beyond curiosity, the study has enormous environmental significance. Noise generated by human activity at sea—engines, industrial sonar, oil drilling—disrupts whales’ lives [5]. If we can understand their language, we may learn when they are stressed, improve buffer zones, and design marine traffic that is more considerate of the delicate world of the giants beneath the waves. When scientists sit in front of computer screens trying to find meaning in faint clicks from the Caribbean, they connect fields that seem worlds apart—marine biology and computer science, human listening and artificial intelligence. If this method continues to develop and more data are added, it will likely be applicable to additional marine species beyond sperm whales. Each scientific advancement like this brings us closer to a deeper understanding of underwater communication among animals, a field that is only now beginning to emerge.

Hebrew editing: Shir Rosenblum-Man

English editing: Elee Shimshoni

References:

- Additional information on sperm whales from NOAA

- A book on the social life and communication of sperm whales

- Project CETI – the international initiative to decipher whale language

- Paper on the Israeli algorithm for identifying sperm-whale sound sources using AI

- Comprehensive review of the impact of industrial noise on whales