Imagine finding a tin box on the shelf meant for storing cookies. You open it, expecting to find a sweet treat, but instead it is filled with buttons, threads, and sewing needles. True, these are not the items the box was designed to hold, yet the box is just as useful! Evolution behaves in a similar way through a process called co-option, in which existing biological mechanisms are utilized for completely new roles. One of the most intriguing instances of this sort of "evolutionary repurposing" can be seen in the formation of the sea urchin’s embryonic skeleton.

Advertisement

Biological “repurposing” of this kind is surprisingly common in nature, especially the repurposing of genetic programs used for building body parts. A genetic program is the manner by which the genetic code stored in DNA is translated into specific proteins in specific cells, ultimately guiding the formation of organs that characterize a particular organism. The differences between the genetic programs encoded in our DNA and those of the sea urchin underlie the large differences in our body structures, even though the genes themselves, and the proteins they produce, are very similar. You can think of it as an instruction booklet for a Lego set: using very similar building blocks, one can create figures that are completely different from one another, since the resulting shape depends on the instructions.

The repurposing we are discussing here occurs when changes in the DNA alter the genetic program so that, instead of building one organ, another organ with a completely different function is formed. There are many examples of this in nature. For instance, the genetic program that builds limbs in certain insects was recruited in the rhinoceros beetle [1] to create its large horns. The phenomenon of co-option raises important questions: when evolution “repurposes” a developmental program, which parts are preserved, which are modified, and which are added to create a new structure?

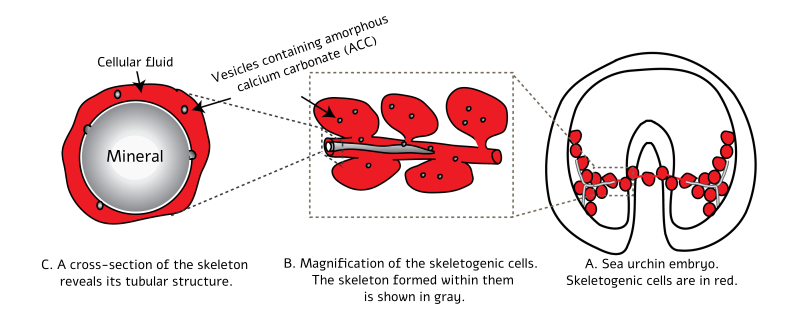

In our research, we examined this by studying how sea urchin embryos build their skeletons. Sea urchins are invertebrates belonging to the phylum Echinodermata, which comprises about 6,500 species. Echinoderms have no vertebrae, yet they possess a skeleton made of tubular, needle-shaped rods (spicules) composed of the mineral calcite. These tubes are produced by dedicated cells (Figure 1A [2]), whose membranes fuse to form a common structure called a syncytium that resembles a cable connecting the cells (Figure 1B). This merged cellular structure creates an internal cavity that fills with calcium carbonate, which crystalizes to become a rigid calcite skeleton (Figure 1B). The inner cavity elongates through the deposition of calcium carbonate at its tips and assumes a tubular shape (Figure 1C).

We investigated the genetic program that builds the sea urchin skeleton and found that it employs the same genes and proteins that vertebrates, including humans, use to build their blood vessels [3]. Specifically, the cells that construct blood vessels in vertebrates and the skeletal spicules in sea urchins use the same inter-cellular signaling systems to guide tube growth. Inter-cellular signaling systems rely on signaling proteins secreted by one cell and receptors on another cell that bind the signal. This triggers mechanisms that instruct the “receiving” cell to migrate toward the “sending” cell. We discovered that a signaling protein called VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) participates in the growth of both vertebrate blood vessels and sea urchin spicules. VEGF acts as a guide that directs cell migration and directly activates the cellular mechanism ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase), which regulates cell movement and gene activation [4].

When we examined whether this program was used by more ancient animals, we found that there, too, it controls the construction of various types of transport tubes. We concluded that echinoderms repurposed this ancient transport program into a program for building a spicule skeleton, whereas vertebrates used it to form blood vessels in their bodies. In both cases the cells create a tubular structure—in sea urchins the tube is filled with mineral, while in vertebrates it is filled with blood. This discovery raised the question: how was the ancient genetic program for building a tube filled with soft fluid, adapted in echinoderms to construct a tube filled with hard mineral?

It turns out that the adaptation was achieved by adding a component to the ancient program that senses the rigid mineral and responds to it [4, 5]. Cellular mechanisms that sense mechanical rigidity are activated in the cells that build the sea urchin skeleton in response to the formation of the hard mineral. In turn, the cells activate ERK, which helps them shape the structure of the skeletal spicules [5]. In other words, sea urchins retained the essential parts of the ancient program, such as the signaling systems, VEGF, and ERK, but added a “hard-structure sensing” component to tailor the program to the unique requirements of building a rigid skeleton.

Our work not only deepens our understanding of sea-urchin development but also provides insights into the remarkable capacity of cellular signaling networks to change and create new organs over the course of evolution. It is a beautiful example of how life repurposes and reshapes ancient construction plans to build the diversity of forms and body structures we see today.

Figure 1: Illustration of skeletal deposition and spicule formation in a sea urchin embryo. (A) A sea urchin embryo at the stage in which two spicules that will become the skeleton are formed. The skeleton-forming cells (aka skeletogenic cells, in red) are connected to one another by a cable they create, within which the spicules develop. (B) Enlargement of the region in (A) where one spicule (in gray) is growing. Here one can see the growth of the spicule inside the cable that spans the skeletogenic cells. It is also apparent that the spicule grows by the deposition of vesicles filled with calcium carbonate into the inner cavity inside the cable. (C) In a cross-section one can see the mineral crystallizing into calcite within the inner cavity. Adapted from “The Glory of the Sea: Strength and Transformation in the Aquatic Systems of Israel” [2].

English editing: Elee Shimshoni

References:

- Rhinoceros beetle, Wikipedia

- ”The Glory of the Sea: Strength and Transformation in the Aquatic Systems of Israel”, Chapter 25 (Hebrew)

- Article on the similarity between the genetic program that builds the skeleton in sea urchins and the program that builds blood vessels in vertebrates

- Article on the connection between ERK and VEGF during elongation of the sea-urchin skeleton

- Article on mechanosensing during skeletal formation in sea urchins