A Google software accurately predicts protein folding—more accurate than the best simulations in the world today. Why is protein folding so important and how is their 3D structure predicted?

Advertisement

Proteins play an extremely important role in biology: they are tiny machines that perform processes critical to cellular function, such as transporting nutrients, regulating metabolic pathways, and building the cell’s structural framework. The human body contains tens of thousands of different proteins, each with a unique function [1]. A comprehensive understanding of how these proteins operate in the body may help identify the causes of many diseases and pave the way toward new treatments.

Proteins are essential for proper bodily function, and their activity depends on their 3D structure: malfunctioning proteins can cause serious harm. A well-known example is Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy, better known as “mad cow disease.” This disease occurs when a specific protein in the cow’s brain changes its spatial conformation in a way that prevents it from functioning and, worse, causes other proteins that come into contact with it to change their shape (in effect “infecting” them). A protein altered in this way is called a prion. A prion that has changed its conformation is resistant to being broken down by cells, and when enough prions misfold they form deposits that disrupt the surrounding cells, quickly leading to severe neurological problems [2].

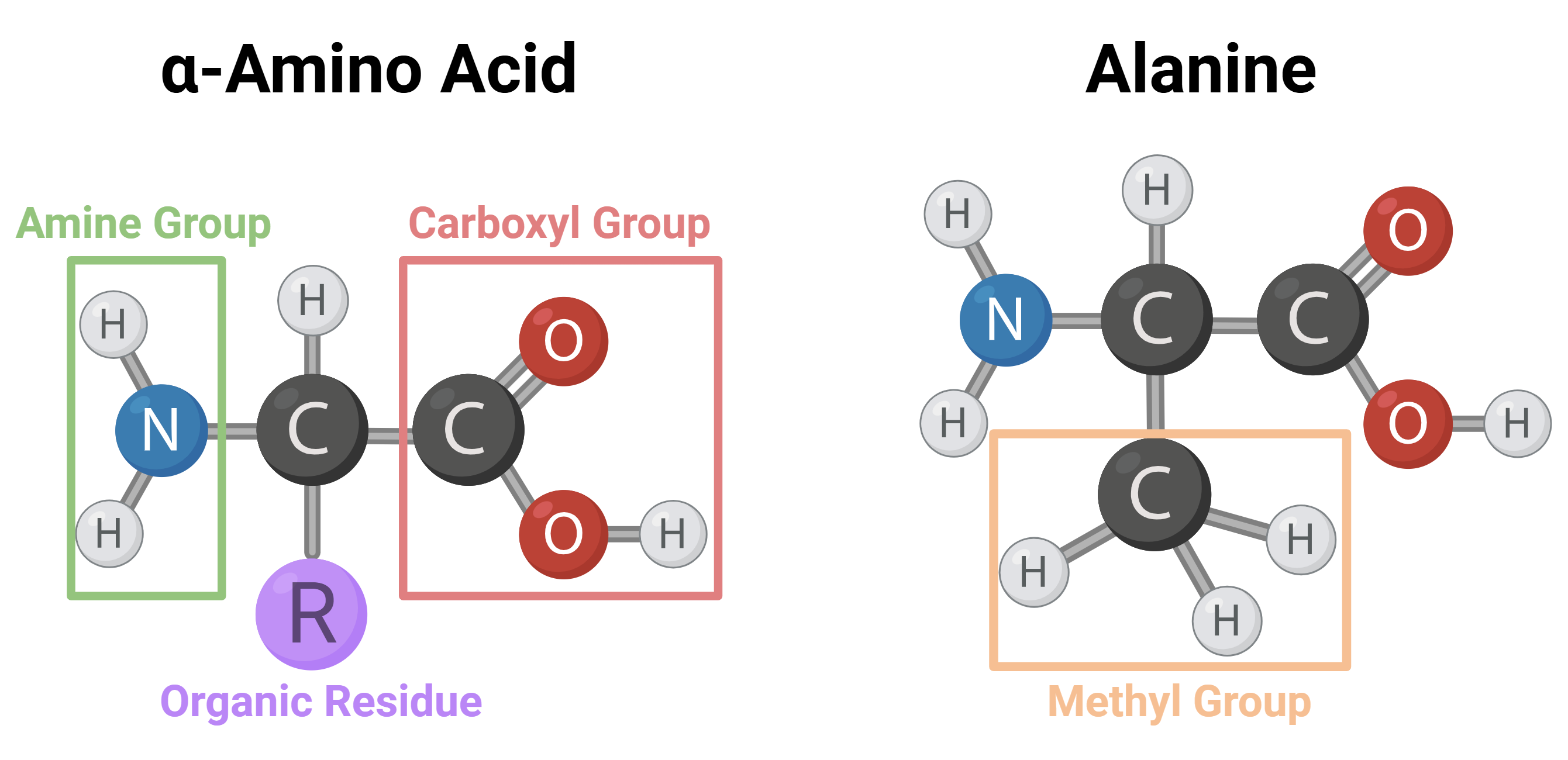

To fully understand how a given protein works, we must know its spatial structure, which, as noted, plays a key role in its biochemical activity. So how are proteins built? At the most basic level, proteins are chains of small building blocks called amino acids, linked together (footnote: specifically α-amino acids). All amino acids share the same chemical skeleton except for a part of the molecule called the “side chain” (residue)—each amino acid has a different residue. Every protein in the human body consists of long sequences of amino acids chosen from 20 different types. These sequences range in length from a few hundred to several hundred thousand of these building blocks.

Left: the general structure of an α-amino acid. Right: the structure of alanine, one of the amino acids essential for normal human function.

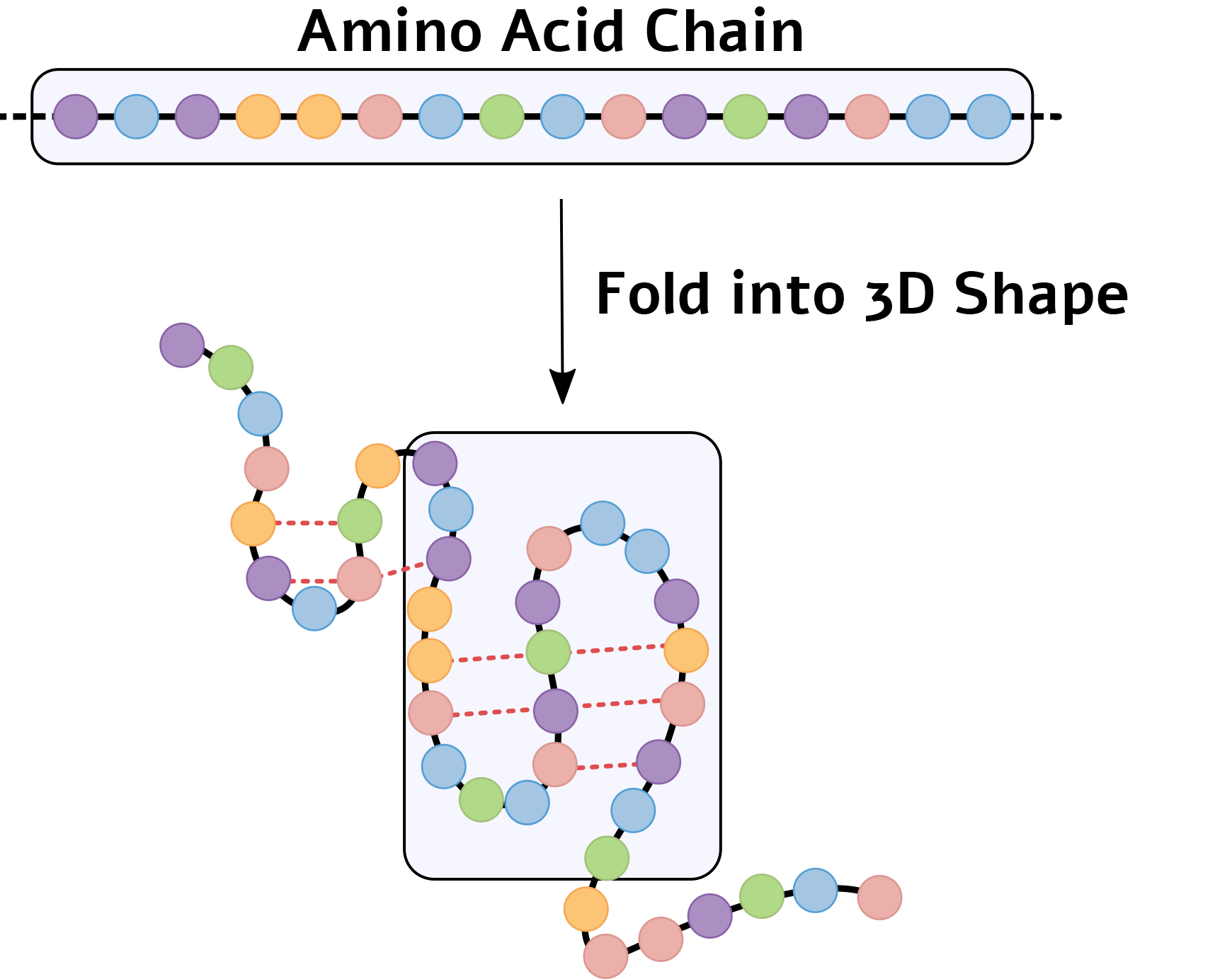

In the human body, proteins are synthesized by the ribosome, whose role is to join α-amino acids into long chains. The different residues along the chain drive it to fold into a specific 3D structure that minimizes the system’s energy: fat-soluble residues tend to face the interior of the structure, whereas water-soluble residues tend to face outward, in contact with the cell’s aqueous environment. Positively charged residues are attracted to negatively charged residues and repelled by other positively charged ones, and so on. It is worth noting that not all proteins fold spontaneously into their optimal shape; some rely on special proteins called "chaperones" to assist in the folding process [3].

A schematic example of the folding of an amino-acid chain into a 3D structure. The 3D shape is stabilized by interactions between different amino acids (dashed red lines).

The protein’s structure is therefore an extremely complex physical system influenced by a very large number of variables. Each protein has many low-energy conformations—sometimes thousands or more. Scientists who study protein structure computationally (i.e., via simulations) face a challenge: which conformation—or which small set of conformations—among the thousands of possibilities is the most stable in the protein’s functional environment? This problem—accurately computing protein folding given its amino-acid sequence—is one of the central challenges in protein research and computational biology today [4]. Massive resources are devoted to simulating and folding various proteins in order to determine their structures and thereby deepen our understanding of how they function.

The most common method for performing these calculations is molecular dynamics: atoms are treated as points in space whose motion is determined by solving Newton’s equations of motion. This motion depends on properties such as their masses, the covalent bonds between them, and how electric charge is distributed over the entire molecule. To keep the calculation as accurate as possible, the simulation advances in tiny time steps, typically on the order of femtoseconds (fs; there are one million billion—10 followed by 15 zeros—femtoseconds in a single second). For medium-sized proteins in a physiological environment (simulations involving a few tens of thousands of atoms overall), even with supercomputers and large clusters using graphics accelerators to speed up calculations, it is currently possible to compute about a million steps in several hours to days [5]. That may sound like a lot, but a million steps of roughly one femtosecond each amount to only a nanosecond (one-billionth of a second), whereas proteins fold on time scales ranging from 50,000 to about 1,000,000 nanoseconds. In other words, even the most powerful supercomputers require many weeks—and sometimes months or more—to compute the folding of a single protein!

Over the years, many methods have been developed to accelerate protein-folding calculations. One such approach is to distribute the calculation across a large number of personal computers and smart devices worldwide, allowing the computation to run in the background when users are not actively using their devices (for example, at night). A well-known project employing this strategy is Folding @ Home [6].

Artificial-intelligence algorithms have become increasingly popular in recent years. One of the most common approaches employs neural networks that generate predictions for complex systems through extensive “training” on existing data [7]. A program called AlphaFold, developed by DeepMind (a Google subsidiary), has for several years achieved the most accurate predictions of protein structures from their amino-acid sequences. The program’s predictions are highly accurate—more than half of the structures it predicted reached 92.4 % accuracy or better compared to experimentally determined structures (e.g., by X-ray crystallography or nuclear magnetic resonance, NMR), far surpassing “traditional” prediction methods [8].

If AlphaFold’s capabilities continue to improve, it could become an important addition to the existing toolkit for predicting protein structures. Each new protein structure enables us to predict the protein’s activity in the body and how various factors influence its behavior, allowing us to better understand biochemical mechanisms—and thereby improve our ability to combat different diseases. A contemporary example is the prediction of the structure of spike proteins on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic [9]. Understanding these protein structures and how they bind to cell-surface receptors enables us to develop treatments that reduce this binding and thus dampen disease severity.

English editing: Elee Shimshoni

References: