In Part I we explained how to enter a circular orbit in space. In Part II we will discuss elliptical orbits, explain what a maneuver is, and how to perform one.

Advertisement

In Part I we told you about the giant Ephraim who put a rock into a circular orbit around Earth. Ephraim threw the rock so fast, which made it go into orbit 100 kilometers above the Earth.

What would happen if Ephraim throws the rock even harder? At first, the curvature of the path will be smaller, and the rock will start moving away from Earth. But just as the rock rose and then fell when Ephraim threw it straight up, gravity will slow it down. Eventually, the rock will move along an oval-shaped path, moving away from Earth at its slowest speed. Then it will come back from the side of the oval.

When the rock hits Ephraim’s hand again, it will be going at the same speed as when Ephraim threw it. We’ll call the farthest point the rock reaches point A, and the closest point (Ephraim’s hand) point B. Physicists call the closest point perigee and the farthest apogee, but we’ll stick with A and B so as not to confuse things too much.

Now imagine that Ephraim throws a spacecraft instead of a rock. The spacecraft can use a rocket engine (or any reaction engine [1]) to increase its own speed. What happens if the spacecraft speeds up in a direction that is not parallel to its current motion? What happens if it does so at the farthest point from Earth (point A)? The spacecraft will, in effect, “throw” itself again from that point. If the spacecraft speeds up at point A, it's oval-shaped path will change shape. The spacecraft speeds up in the same direction, so point A will remain part of the trajectory. In other words, the spacecraft will make a loop and return to point A. Just as the rock went back to the place from which Ephraim threw it, the spacecraft will return to the point where it fired its engines. What will the added speed be used for? The extra speed will raise the orbit. After the maneuver, the spacecraft will not return to point B at the height of Ephraim’s hand; it will pass at a higher point. The whole orbit will be higher, except at point A. The speed at the new point B (the one above Ephraim) will be lower than the speed at which Ephraim originally threw it, because the energy the spacecraft added was used to go higher.

If the spacecraft changes its speed repeatedly at different points along the orbit until the speed at point A and the speed at the new point B are the same, it will move in a circular (not elliptical) orbit, but this time it will be higher above Earth.

When a spacecraft changes its speed at any point in its orbit, the orbit changes. This is called a “maneuver.” In such maneuvers, the spacecraft fires its engines to change its speed in the direction of motion. If you go faster, the spacecraft will go higher. If you go slower, it will go lower. Remember that the maneuver does not change the altitude at the point where the spacecraft is engaging its engine. It only changes the altitude at other points along its path. The biggest effect happens at the opposite point in the orbit—on the other side of Earth (or the other relevant celestial body). There are also maneuvers that add speed in a direction perpendicular to the orbit, but these do not change the height of the orbit. Instead, they change the plane in which the orbit lies (the imaginary plane around Earth in which the ellipse or circle is “drawn”).

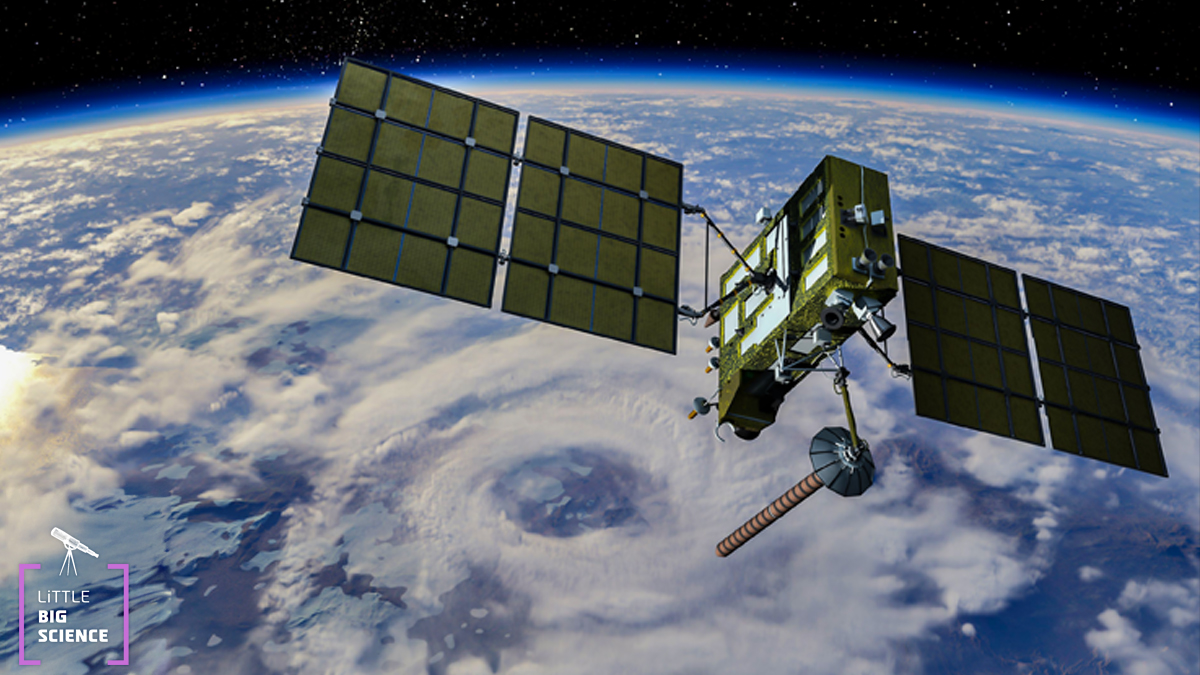

It is hard to build a spacecraft capable of performing altitude maneuvers accurately, because it is difficult to make sure the rocket engines are perfectly aligned with the direction of motion. It is also difficult to control the spacecraft’s position and to determine the position and angle of its engines relative to the orbit, due to slight oscillations of every spacecraft around itself. Another challenge is working out the exact orbital path of the spacecraft. A spacecraft or satellite doesn't know its position in absolute terms. It also doesn't know which orbit it is following at a given moment. To deal with this, we use a ground station that determines the satellite’s position at several points along its orbit. Using this information, we can recreate the real orbital path traced by the spacecraft. Now that we know the orbital path, we can work out what speed and at which point we need to apply it, in order to achieve the desired change to the orbit.

These maneuvers are routine for ordinary satellites, such as the Amos satellites, where the maneuvers keep the orbit in place against various disturbances. However, it is very difficult to build a spacecraft that will execute a series of maneuvers that will send it on a path to reach the Moon. But that is exactly what the scientists and engineers of SpaceIL did. The spacecraft Beresheet was launched into space on a SpaceX rocket. After it separated from the launch vehicle, Beresheet performed several maneuvers to increasingly higher orbits until it reached close enough to the moon. It then maneuvered to change from an Earth orbit to a lunar orbit, which is a complex maneuver in itself, and finally lowered the altitude of its lunar orbit until it hit the Moon!

To sum up Part II—maneuvering in space is hard. Reaching the Moon is very hard. Well done to those who succeeded!

Original animations: Inbari Finkelstein

English editing: Gloria Volohonsky

References: