Advertisement

Monosodium glutamate (abbreviated MSG) is a crystalline substance with a unique flavor characterized simply as “umami”. There is a common claim that the body distinguishes between five separate tastes, each with a different chemical characteristic: sour (acids), sweet (sugars), bitter (bases), salty (salts), and umami. In Japanese, umami means “pleasant savory taste,” and this is indeed a prominent feature. MSG is added to many foods and food products, such as snacks, in order to enhance their flavor.

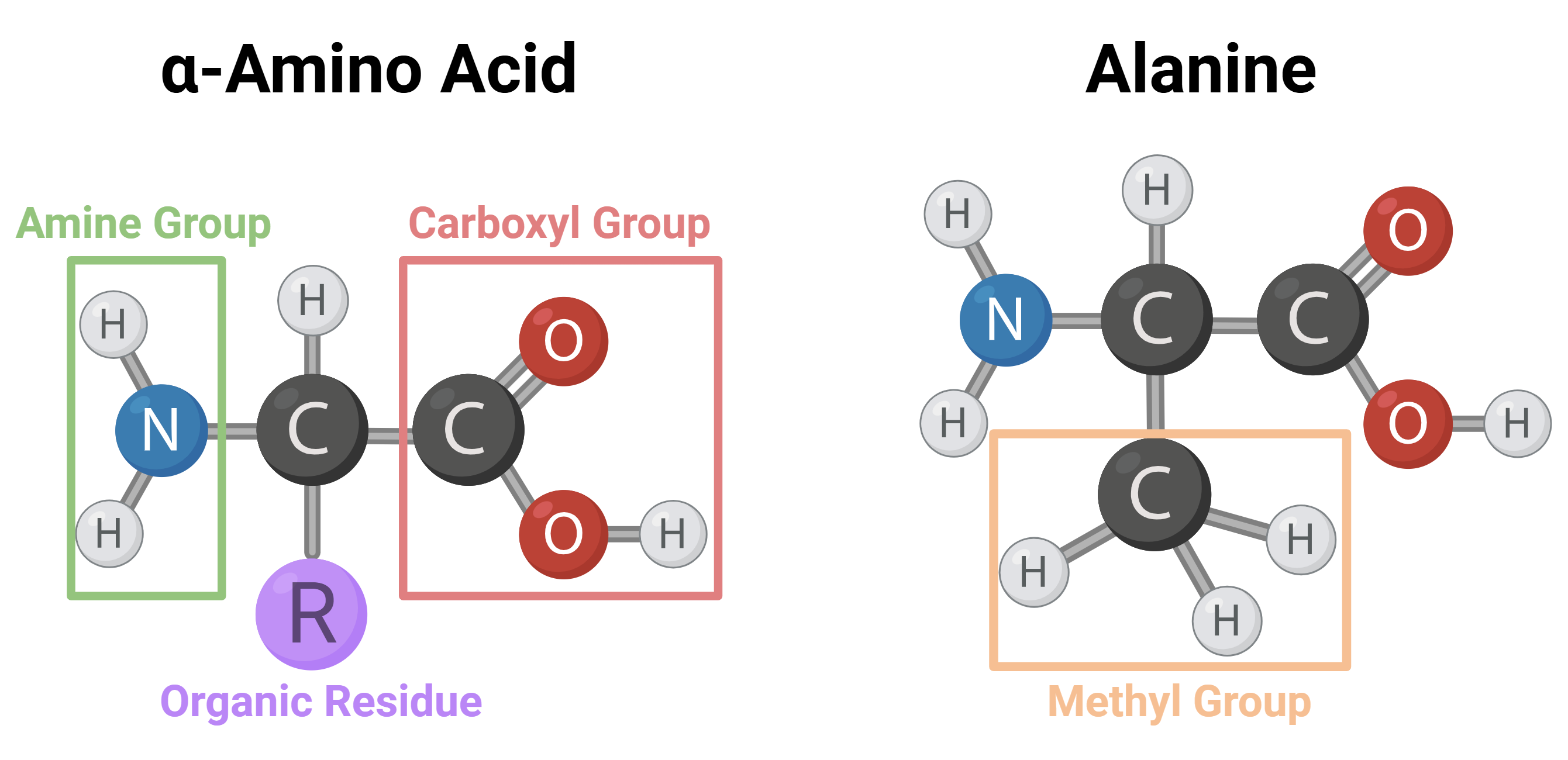

MSG is in fact the sodium salt (sodium, Na) of glutamic acid—an amino acid that is extremely important for proper bodily function. Amino acids are carboxylic acids that also contain an amine group, which is a nitrogen bonded to two atoms, each of which is either hydrogen or carbon. What are carboxylic acids? In principle, a carboxyl group is a carbon atom bonded to one oxygen by a double bond and to a hydroxyl group (oxygen bonded to hydrogen) by a single bond. The hydrogen attached to the oxygen can detach from the molecule, leaving its electron behind; it thus functions as a proton (positively charged) and can bind to other molecules. The carboxyl group, in turn, remains negatively charged (due to the extra electron), with the charge concentrated mainly around the oxygens.

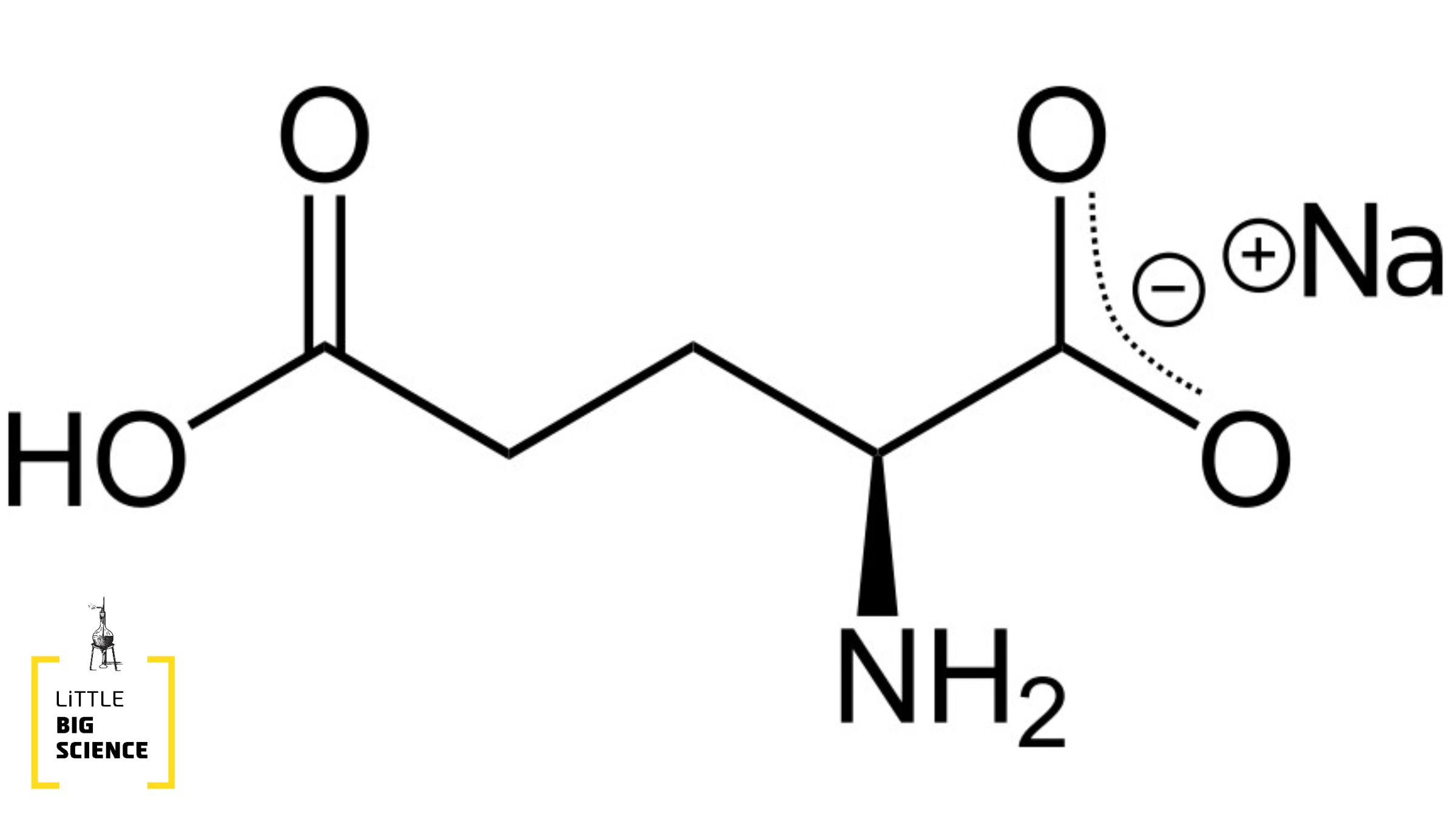

Glutamic acid (right) and the glutamate ion (left)

When a molecule has a carbon atom bonded on one side to a carboxyl group and on the other to an amine group, we call it an “alpha-amino acid,” because the amine and the carboxyl group are “alpha” to each other—in this context, “alpha” means that only a single atom separates them. Of course, the carboxyl and amine groups can be separated by two carbon atoms (beta), three (gamma), and so on. In this article we will refer only to alpha-amino acids, which we will simply call “amino acids.”

Beyond the carboxyl group and the amine, the central carbon in an alpha-amino acid is bonded to two additional atoms: a hydrogen and a carbon that is in turn bonded to other atoms (if the central carbon is bonded to two hydrogens, the molecule is specifically glycine). There are two possible arrangements for the different groups attached to this carbon, designated R and S. Another way to denote the two configurations is with the letters D and L. This method is based on a physical property—the rotation of the plane of linearly polarized light. Amino acids found in nature occur predominantly in the L configuration, for reasons that are still being investigated and that arouse great interest in the scientific community.

As noted, if we look at the central carbon in an amino acid we see that three groups are always attached to it: a carboxyl group, an amine, and a hydrogen. The fourth group is variable and can be any organic side chain (hydrogen, a carbon bonded to three hydrogens, a long hydrocarbon chain, and so on). This is how we classify amino acids: according to the organic side chain. This side chain can be water-soluble or fat-soluble; carry a positive charge, a negative charge, or no charge at all; be composed of a hydrocarbon chain, an aromatic ring, or any other chemical structure. In nature, 21 different amino acids are commonly found in eukaryotes.

A schematic drawing of an amino acid: carbon atoms are black, hydrogen grey, oxygen red, and nitrogen blue. It is important to remember that this is only a schematic illustration! In reality the molecule is not two-dimensional, and the spatial structure is more complex.

Why are amino acids so common in nature? The answer lies in the fact that the amine group of one amino acid can be linked to the carboxyl group of another (a peptide bond), thereby creating very long chains of amino acids (polypeptides). These chains fold in three-dimensional space in a manner that depends on the nature of their side chains, thus forming proteins. The diversity achievable from a relatively small number of amino acids is enormous, and biological systems use them to build highly complex mechanisms. Humans specifically require each of these 21 amino acids, but our bodies can synthesize some of them from others through various biochemical reactions. Thus, we need to obtain only nine of them from our diet [1].

Polypeptide: R denotes organic side chains, while the blue boxes denote the peptide (amide) bonds between the different amino acids.

Back to glutamic acid: in this acid the side chain is actually propanoic acid—three carbons linked in a chain, with a carboxyl group attached to the last one. Glutamic acid is very important for the continuous cellular function of humans and most animals, chiefly in the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle), glycolysis, and gluconeogenesis—processes critical for energy conversion and storage in cells. In addition, glutamic acid serves as one of the most abundant neurotransmitters in the body and is involved in a variety of processes, including learning and memory. Glutamic acid is the precursor for the biosynthesis of the molecule GABA, another important neurotransmitter. In other words—without glutamic acid, we could not function.

The importance of glutamic acid might provide an explanation for why its sodium salt tastes so good: evolutionarily, we developed a preference for foods containing this acid to maintain proper bodily function. The glutamate salt can be found in a variety of foods such as tomatoes, seaweed, cheese, and more. Industrially, the salt is produced mainly for flavoring purposes, by fermenting sugars in the presence of the bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum.

There are many rumors surrounding MSG, claiming that consumption of the salt can lead to headaches and joint pain. The source of these rumors is likely a 1968 letter by Robert Ho Man Kwok to the New England Journal of Medicine, in which he described side effects he experienced after eating in Chinese restaurants (hence the term “Chinese restaurant syndrome”). The experiences described were general and could have been caused by a variety of factors; Kwok indeed listed several possible causes, including alcohol and sodium. However, studies conducted on the subject (including double-blind studies—in which the participants did not know whether they had consumed the substance or not) found no connection between MSG consumption and any side effects [2]. Of course, this does not mean that there might be an upper limit for consumption of glutamic acid or its salts.

English editing: Elee Shimshoni

References: