Advertisement

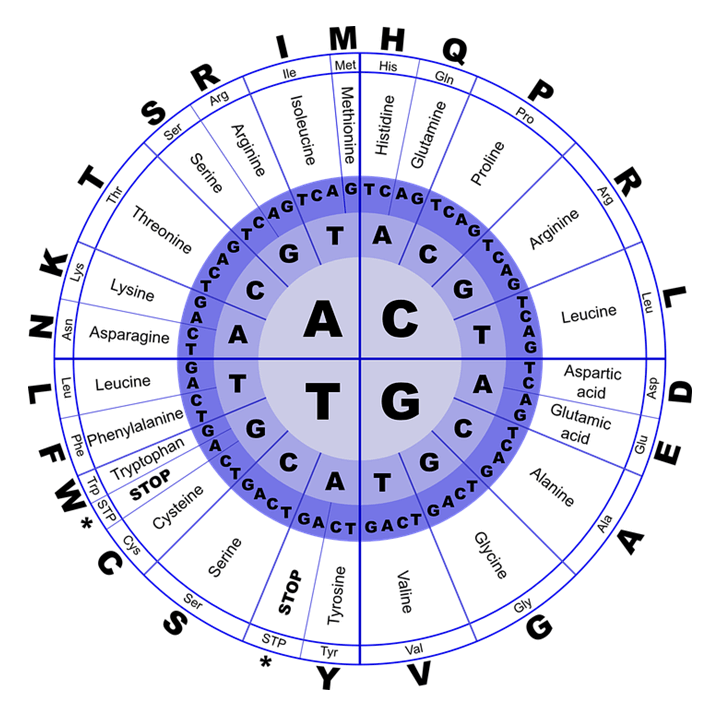

A bit of molecular background: The hereditary material, namely DNA, contains all the information required for life. This information is encoded in what is known as the “genetic code.” DNA is built from building blocks (nucleotides), whose sequences fulfill various roles: protein encoding, regulation, structural stability, and so on. In protein-coding regions, every triplet of nucleotides (denoted by the letters G, A, C, and T) forms a “codon” that specifies a particular amino acid (of which there are 20). When linked together, these amino acids ultimately build the various proteins. Because there are 64 different codons (the number of possible triplet combinations of four nucleotide types), there is more than one codon per amino acid. Three codons function as stop codons, whose role is to terminate elongation of the amino-acid chain (i.e., the nascent protein).

It is important to note that the genetic information in DNA does not pass directly to the protein assembly site—the ribosome, whose structure was deciphered, among others, by Prof. Ada Yonath. The mediating molecule is messenger RNA (mRNA), which is constructed based on the DNA. RNA resembles DNA in structure and likewise contains four nucleotides corresponding to those in DNA, but in RNA the nucleotide U is present in place of T.

Cells contain a complex machinery of proteins and assorted RNA molecules whose task is to read the code and build the required protein accordingly. The key molecule that matches codon to amino acid is transfer RNA (tRNA), which couples the genetic code to the appropriate amino acid that has been loaded onto it by a specific enzyme.

The genetic code assumed its present form apparently before the split into the three superkingdoms (bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes), because it is identical in all three. Only a handful of exceptions are known, such as codons for one amino acid that encode for another, or stop codons that encode for an amino acid, which likely evolved later.

In one particular group of yeast (unicellular fungi) a documented deviation occurs in a codon that encodes an amino acid. The codon appearing in DNA as the sequence CTG (in RNA—CUG), which in most other organisms encodes the amino acid leucine, encodes the amino acid serine in some of these yeast and alanine in others.

Recently, a joint team, ked by Stephanie Mühlhausen and Laurence Hurst from the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath, UK, and Martin Kollmar from the Max Planck Institute in Germany—discovered that in a particular yeast of this group, Ascoidea asiatica, the CUG codon is translated randomly as leucine or serine, a phenomenon not previously observed.

Closer analysis revealed that this fungus possesses two distinct genes encoding tRNA molecules that recognize the CUG codon. One matches the original amino acid (leucine) to the codon, while the other matches serine. Consequently, whenever the CUG codon must be translated, it is interpreted stochastically according to the tRNA that happens to be available.

Biochemically, serine and leucine differ greatly in size and in other properties (e.g., serine is hydrophilic, while leucine is hydrophobic). Substituting serine for leucine within the amino-acid chain can alter the three-dimensional structure and alter the protein’s activity. So how does the fungus cope with the challenge posed by two tRNAs that encode different amino acids for the same codon? It turns out that in most relevant positions the original CTG was apparently replaced, through random mutation followed by natural selection, by one of the other leucine codons. If a CTG codon remains at a particular site within some protein, it is presumably a location where changing leucine to serine does not hinder proper protein function.

The researchers, who estimate that the fungus has carried both tRNA types for roughly 100 million years, wonder what advantage, if any, this conferred, allowing the phenomenon to persist and become fixed in the population.