Advertisement

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria pose a very serious problem in hospitals in Israel and around the world. In Israel alone they claim the lives of at least about 5,000 people every year—people who entered the hospital for treatment of some illness, were exposed to one of these strains, and did not leave the hospital because of it.

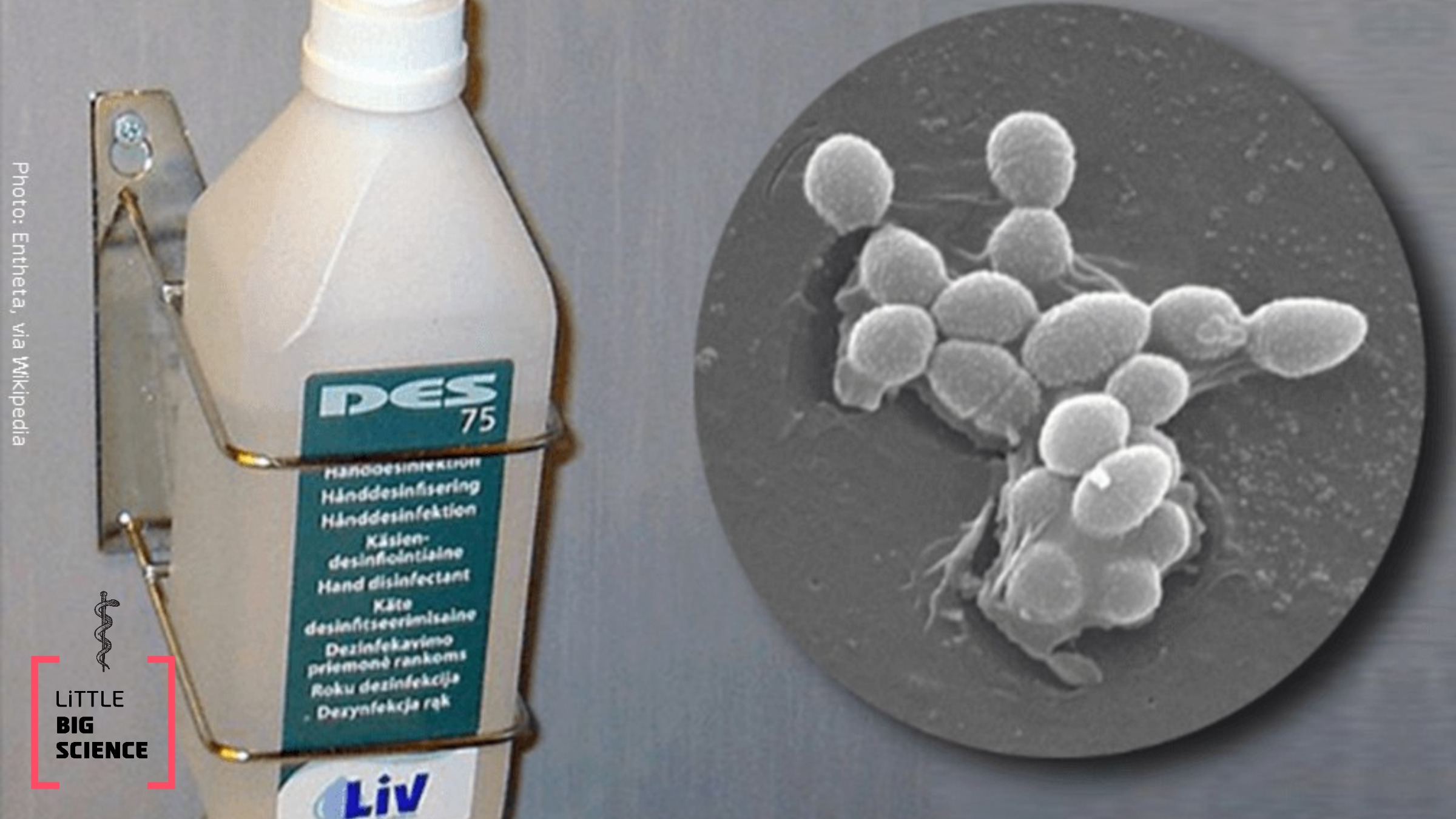

One solution that helps tackle these resistant bacteria is alcohol-based hand disinfectants—70% ethanol or isopropanol—distributed throughout hospitals, and if medical staff and visitors make sure to use them, they can indeed help prevent the transfer of bacteria between patients.

Indeed, over the past 15 years medical staff and visitors have diligently used disinfectants, and since then a significant decline has been observed in the number of patients infected with antibiotic-resistant strains of the pathogenic bacteria Enterococcus faecium and Staphylococcus aureus. The disinfectants are also effective against other hospital pathogens.

However, as reported in early August 2018 by an Australian research team led by Paul Johnson and Timothy Stinear of the University of Melbourne, after the decline, a real increase began in Australian hospitals in the number of patients infected with E. faecium. These bacteria are resistant to antibiotic drugs. Such an increase did not occur with S. aureus, so at least for the latter it was clear that the use of disinfectant is effective.

E. faecium bacteria are part of our natural gut microbiota. They are harmless to healthy people, but antibiotic-resistant strains can infect hospital patients and mainly cause urinary-tract infections and sepsis.

CDC/ James Archer, 2013

The researchers searched the refrigerators of two Melbourne hospitals and located 139 different isolates of E. faecium—each of which had caused disease in a different person—collected between 1997 and 2015, a span of 19 years. The researchers examined how many survived out of 100 million bacteria from each isolate after five minutes in a 23% isopropanol solution. It turned out that the later isolates, after 2010, were much more resistant to the disinfectant solution than the earlier isolates—a phenomenon called alcohol tolerance.

The researchers compared the genetic material of disinfectant-resistant and disinfectant-sensitive bacteria. In the resistant ones they found several different mutations in genes related to sugar metabolism, and these mutations cause the bacteria to be alcohol tolerant/resistant. To confirm the findings, the researchers disrupted those mutant genes, thereby restoring the bacteria’s sensitivity to the disinfectant.

So far the phenomenon has been observed only in Australia, but it definitely needs to be investigated in hospitals elsewhere in the world. Patients, visitors, and hospital staff from these hospitals could have transferred these bacteria to other places; they did not necessarily arise there independently. Did the bacteria evolve in Australia? Perhaps someone brought them there. Important to emphasize that, aside from E. faecium, the other hospital bacteria are indeed sensitive to hand disinfectants, and their use should continue.

As for E. faecium—a local solution will have to be found wherever disinfectant-resistant bacteria are discovered, starting with isolating the patients and cleaning their environment by other means, perhaps chlorine-based compounds that would kill them.

Interview with the lead researcher about the study: