Advertisement

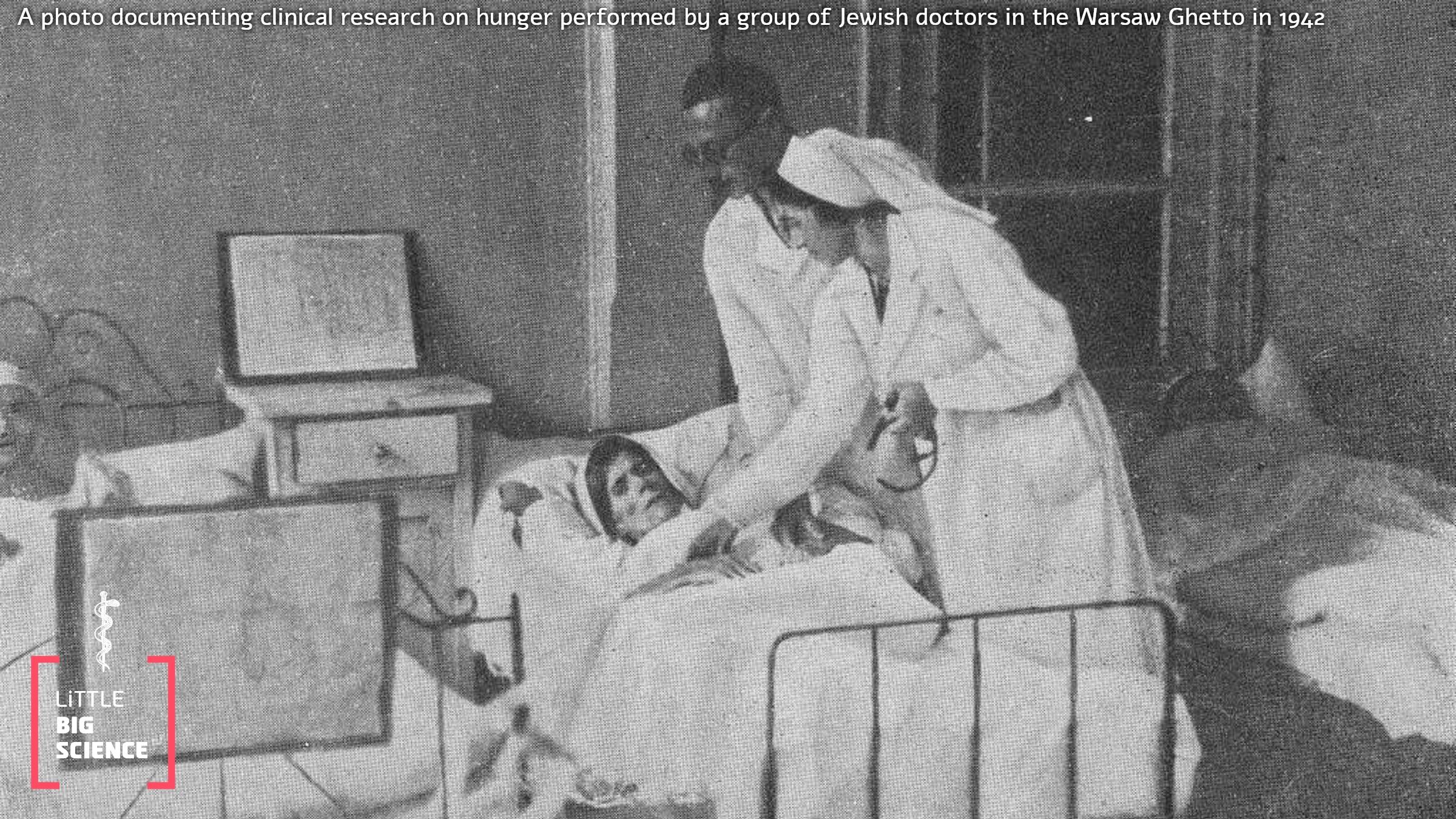

In honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day, the following post describes one of the unexpected causes of death that claimed an unknown number of victims who survived the Nazi inferno—Refeeding Syndrome. Unfortunately, the syndrome was discovered and characterized only after World War II, mainly through research on survivors of Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, yet many survivors of the extermination camps suffered from it as well.

Refeeding Syndrome occurs in people that endured a prolonged period of starvation upon their return to a regular diet, i.e., a diet that is richer and more calorie-dense. It manifests as a sharp decrease in blood levels of potassium, magnesium, and phosphate. The explanation is metabolic-hormonal: during starvation, the body receives insufficient nutrients, especially those that provide energy—glucose and fat. As a result, the body turns to breaking down its energy reserves, primarily glycogen, which is depleted relatively quickly, followed by proteins and fat stores. At the same time, several additional nutrients continue to work at full speed to regulate metabolism: potassium, which controls fluid balance; phosphate, which participates in the production of ATP, the body’s energy currency; thiamine (vitamin B1), which plays a key role in metabolism; and magnesium, which helps maintain ATP and is an essential cofactor for many enzymes.

When feeding resumes, significant hormonal shifts occur. Glucagon—responsible for breaking down glycogen—drops dramatically from its previously high levels, while insulin surges, driving glucose into the cells too rapidly. To meet metabolic demands, the body continues to draw on the stores of the aforementioned vitamins and minerals, lowering their levels even further. The result is an acute deficiency of these nutrients and a sharp drop in their blood concentrations, accompanied by a drastic fall in blood sugar—an effect that impacts every organ. In the brain, this manifests as seizures marked by partial loss of consciousness and involuntary movements, and, in extreme cases, coma. The syndrome also affects the respiratory system and the heart. Tragically, Refeeding Syndrome can indeed be fatal.

Treatment usually includes intravenous thiamine, slowing the rate of feeding, and a gradual return to a full diet. Today, the syndrome is encountered quite frequently in internal and geriatric hospital wards, when malnourished elderly patients are admitted and receive full refeeding, mainly via non-oral routes: enteral (directly into the gastrointestinal tract, for example through a feeding tube) or parenteral (intravenously).

A personal note: my maternal grandmother, the late Sarah Rosenberg, was a Holocaust survivor. After a fortunate escape from a death march by pretending to be dead, and following forced labor in Austria manufacturing grenades, Sarah found shelter in a nearby village, where she discovered a full chocolate bar. Until her dying day, chocolate was among her favorite things—and it was then as well. With remarkable wisdom and instinct, she resisted the urge to devour the entire bar at once and instead consumed it piece by piece, slowly. That restraint likely saved her from the same fate that, unfortunately, took the lives of too many survivors who endured the inferno but not this wretched syndrome.

English editing: Elee Shimshoni

References:

- on the initial characterization of the syndrome immediately after WWII

- a review about the syndrome

- another review of the syndrome