The James Webb Space Telescope was launched yesterday, on its way to settle around the second Lagrange point (L2), located 1.5 million kilometers from Earth. Lagrange points are positions in space where a body will remain in a stable orbit and at an approximately constant distance relative to Earth and the Sun. There are five such points—placing the telescope specifically at L2 will facilitate the use of sensitive instruments that require protection from solar radiation.

Advertisement

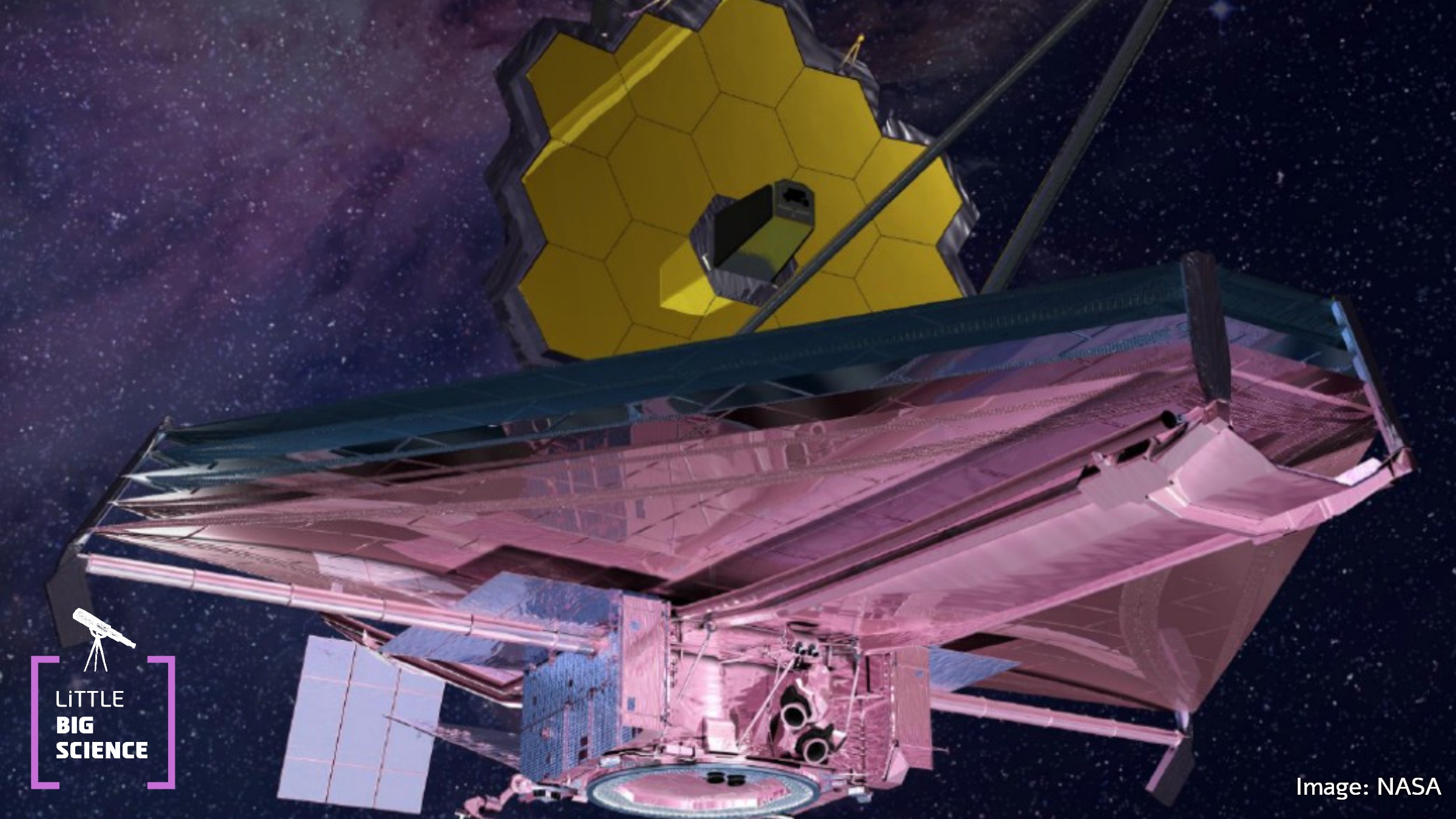

On 25/12/2021, NASA’s flagship project in astronomy and cosmic exploration—the James Webb Space Telescope—was launched. This telescope is designed to replace the Hubble Space Telescope [4] and to enable a significant leap forward in humanity’s ability to observe the universe.

The new space telescope incorporates many technological innovations, from the aperture of its primary mirror to advanced cooling systems. Yet one important innovation is not technological at all: it is the destination to which the telescope was launched. The Hubble Space Telescope, which revolutionized our view of the stars, orbits Earth in low Earth orbit at an altitude of about 550 km. James Webb, by contrast, will be stationed roughly 1.5 million km from Earth—more than four times farther than the Moon. Why there, of all places?

The reason for this distance is that the satellite will be positioned at the Lagrange point L2.

What is a Lagrange point? Let us examine the forces acting on a body in space (e.g., a satellite, an asteroid, a planet, etc.). When a body is near a much larger one, the larger body’s gravity dictates its orbit. The orbital motion is described by Kepler’s laws [1, 2]. This is the case for Hubble—it is in a low orbit around Earth, and in order to describe its approximate path we can neglect other forces. It is not that other bodies exert no influence, but their effect on the exact orbit is small. For our purposes, Hubble travels around the Sun together with Earth, and the Sun hardly affects its motion around Earth. Here we can separate the influences of the Sun and Earth.

But what happens when we move a bit farther away? In that case the gravitational pull of more than one “large” body becomes significant. Let us call them the “large body” and the “intermediate body.” For example, in the Sun–Earth system, the large body is the Sun, the intermediate body is Earth, and the small body is our telescope. This is a complex system, and the small body’s orbit cannot be described in a simple manner. However, there are several special cases in which this is not so: the small body’s motion can then be described relatively simply, and we can exploit that fact to our advantage.

Let us return for a moment to the simpler situation of one large body and one small body. Kepler’s laws [1, 2] tell us how long it takes the small body to orbit the large one. This period is calculated based on the mass of the large body and the distance of the small body from it. Why is mass important? Because it determines the gravitational force that drives the small body’s orbital motion. The farther we move from the large body, the longer the orbital period becomes.

When we insert an intermediate body between them, we introduce another gravitational pull that affects the small body’s orbit. This force is significant and although the intermediate body’s mass is much smaller than that of the large body (the Sun's mass is about 300,000 times that of Earth), gravity decreases with the square of the distance—that is, if we triple the distance, the gravitational force drops by a factor of nine. Because the small body is relatively close to the intermediate body, it also feels its gravity.

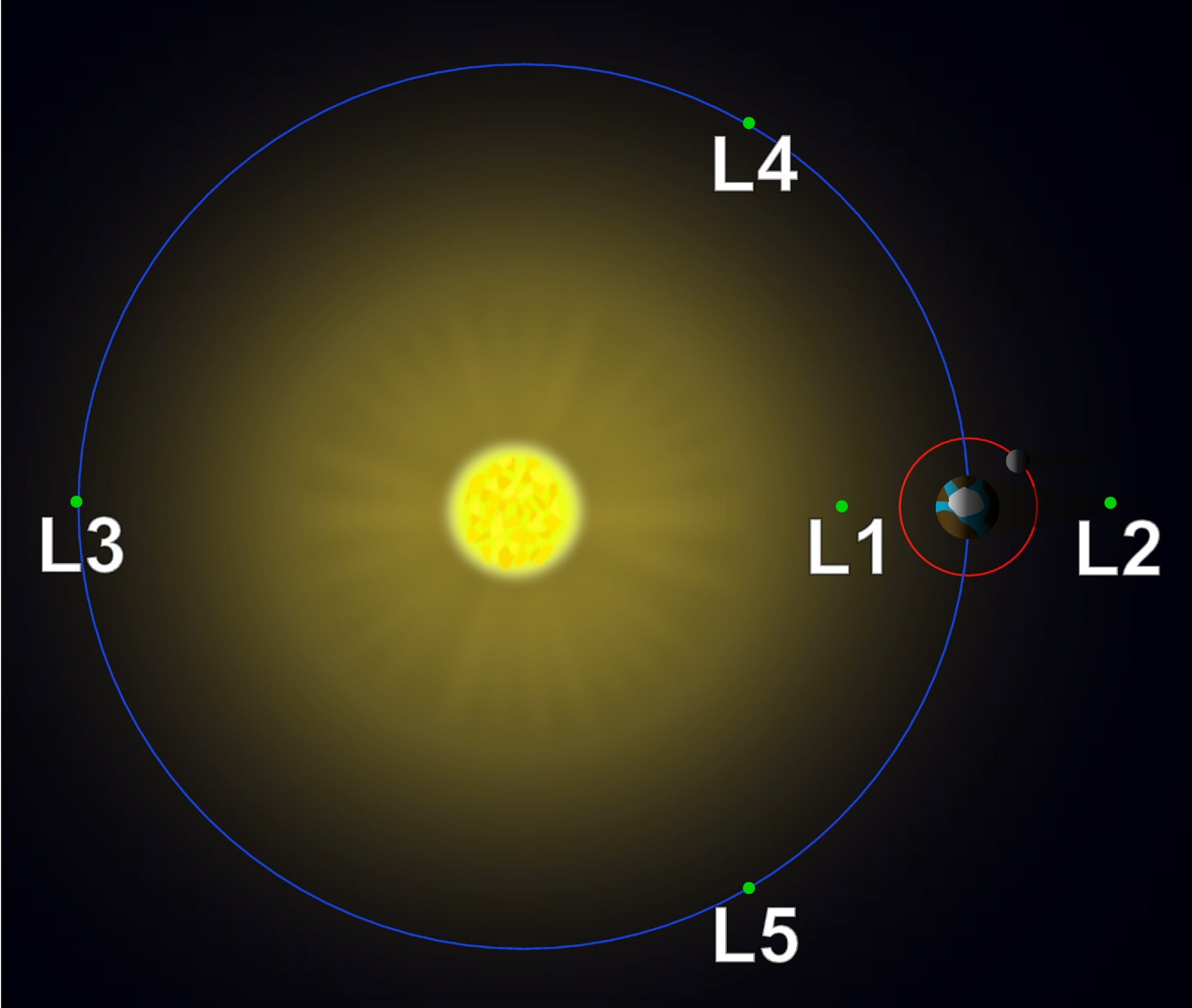

Now suppose we want the small body to remain at a fixed point relative to both the large body and the intermediate body. Calculations show that five such points exist; they are called “Lagrange points,” after the mathematician who computed them (see illustration below). Three lie on a straight line connecting Earth and the Sun and beyond them: one between Earth and the Sun (L1), one beyond Earth (L2), and one beyond the Sun (L3). These are unstable points and any small disturbance will push the small body out of orbit. Therefore, James Webb still needs thrusters to stay near L2. Two additional points, L4 and L5, are stable and are also used by various spacecraft [3]. At every Lagrange point, the small body’s orbital period around the large body equals the intermediate body’s orbital period around the large body.

Image: Xander89, wikimedia.org

So why place our telescope precisely at the unstable L2 rather than at one of the stable points? The reason is that the telescope operates in the infrared range. Infrared sensors require low temperatures, and sunlight heats the telescope. To protect the instrument, a sunshield was installed to block the Sun. Because Earth lies between the satellite and the Sun, the amount of radiation reaching the telescope is reduced, and the shield can be oriented toward a single direction, blocking both the heat coming from the Sun and the heat radiating from Earth, which would be required at the other Lagrange points. This is done without constantly adjusting the shield as the Sun’s position changes relative to the telescope, as would be necessary in an orbit like Hubble’s.

James Webb is not the first telescope to be stationed at L2. From 2009 to 2013 the European Space Agency’s Herschel telescope was stationed there, but it was moved once its coolant ran out. The hope is that James Webb will remain protected from heating for much longer and will provide images and information about the universe that have so far been beyond our reach. We will be here, waiting for a breakthrough in exploring the cosmos.

Hebrew editing: Yinon Kachtan

English editing: Elee Shimshoni

References:

A very cool video on NASA’s site about the telescope’s trajectory at the L2 point