Ever wondered why flight routes do not appear as straight lines on a map? The answer lies in the fact that a map is a (futile) attempt to flatten the Earth. And what does this have to do with the direction towards which people pray?

Advertisement

Between any two points there is an infinite number of paths. Among all those paths, which one is the shortest?

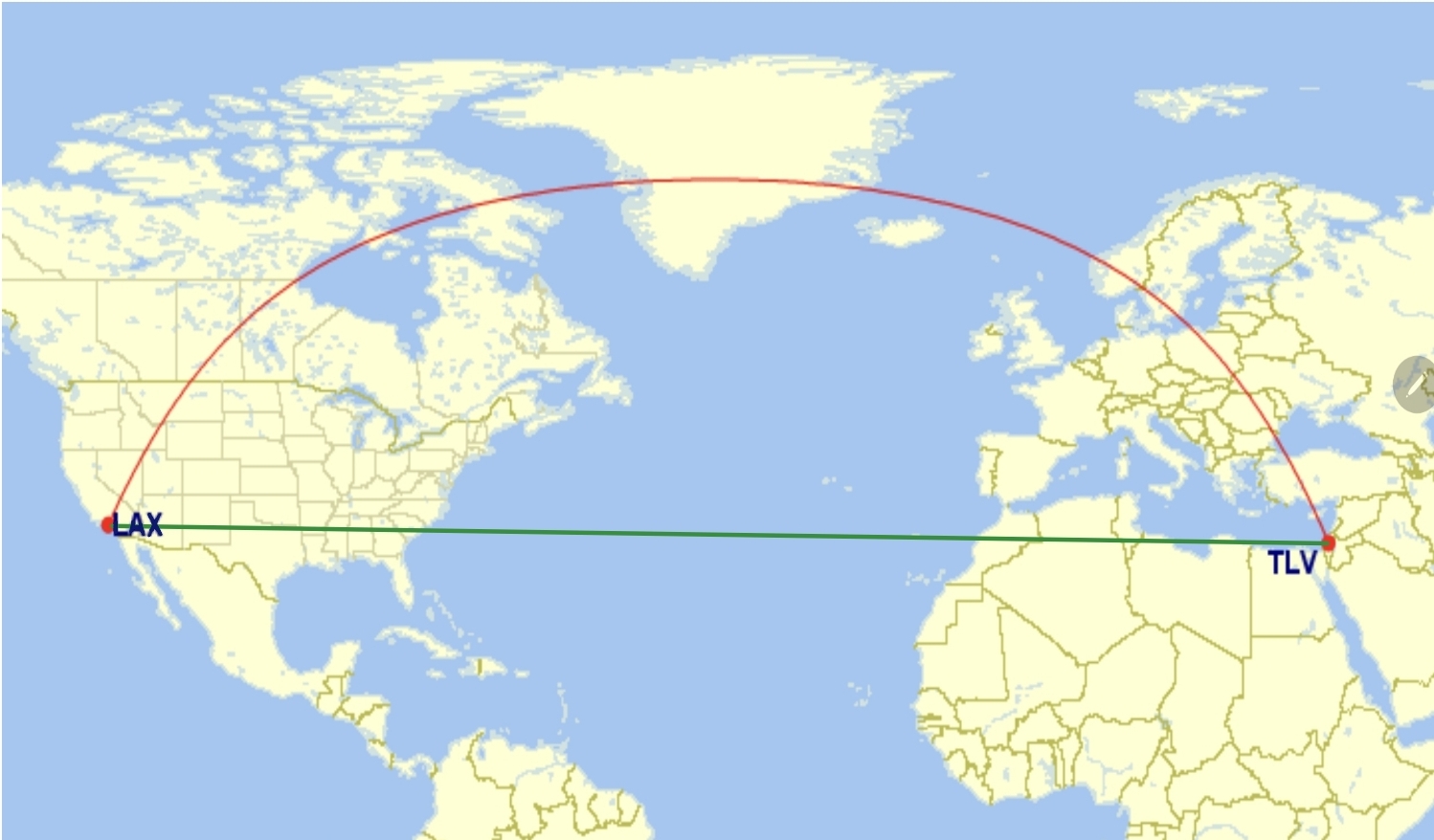

“A straight line!” you will surely answer at once. Indeed, if the two points lie on a sheet of paper, it is clear that we can draw a straight line between them and that will be the shortest path. Even if we take that sheet with the line drawn between the two points and roll it into a cylinder, the shortest path will remain that straight line (unless, after we glue the sheet into a cylinder, an even shorter path appears further along the line we drew). Yet, you may have looked at the flight map projected on an airplane screen on your way to vacation and wondered why the route does not look like a straight line but rather like an arc. The flight route from Tel Aviv to Los Angeles, for example, passes over… Greenland! (See Illustration 1) Airlines certainly have no interest in wasting costly fuel and will always prefer the shortest route. So what is going on?

Illustration 1: The shortest route between Tel Aviv and Los Angeles is actually the red one, which appears curved (and passes over Greenland!), rather than the green one, which appears as a straight line connecting the cities on the map. The image was created using this website [4].

Another way to think of it: imagine you have wrapping paper and a present to wrap. Wrapping a book is simple, wrapping a can of Pringles is also fairly simple, but wrapping a basketball… it will probably not turn out so neat. In addition, you will need wrapping paper with an area larger than the ball’s surface area, because there will be many creases and overlaps.

The tears in the orange peel and the overlaps when wrapping the soccer ball express the built-in distortion of distances when one tries to flatten a sphere. Therefore, the geometry that describes the sphere does not match the flat geometry (namely the Euclidean geometry we learned in school). The sum of angles in a triangle is 180 degrees? Not on a sphere. Parallel lines never meet? Here they do! It is not that you were lied to, it is simply that everything you learned was on a plane, whereas on a surface like a sphere the rules are different [1,2].

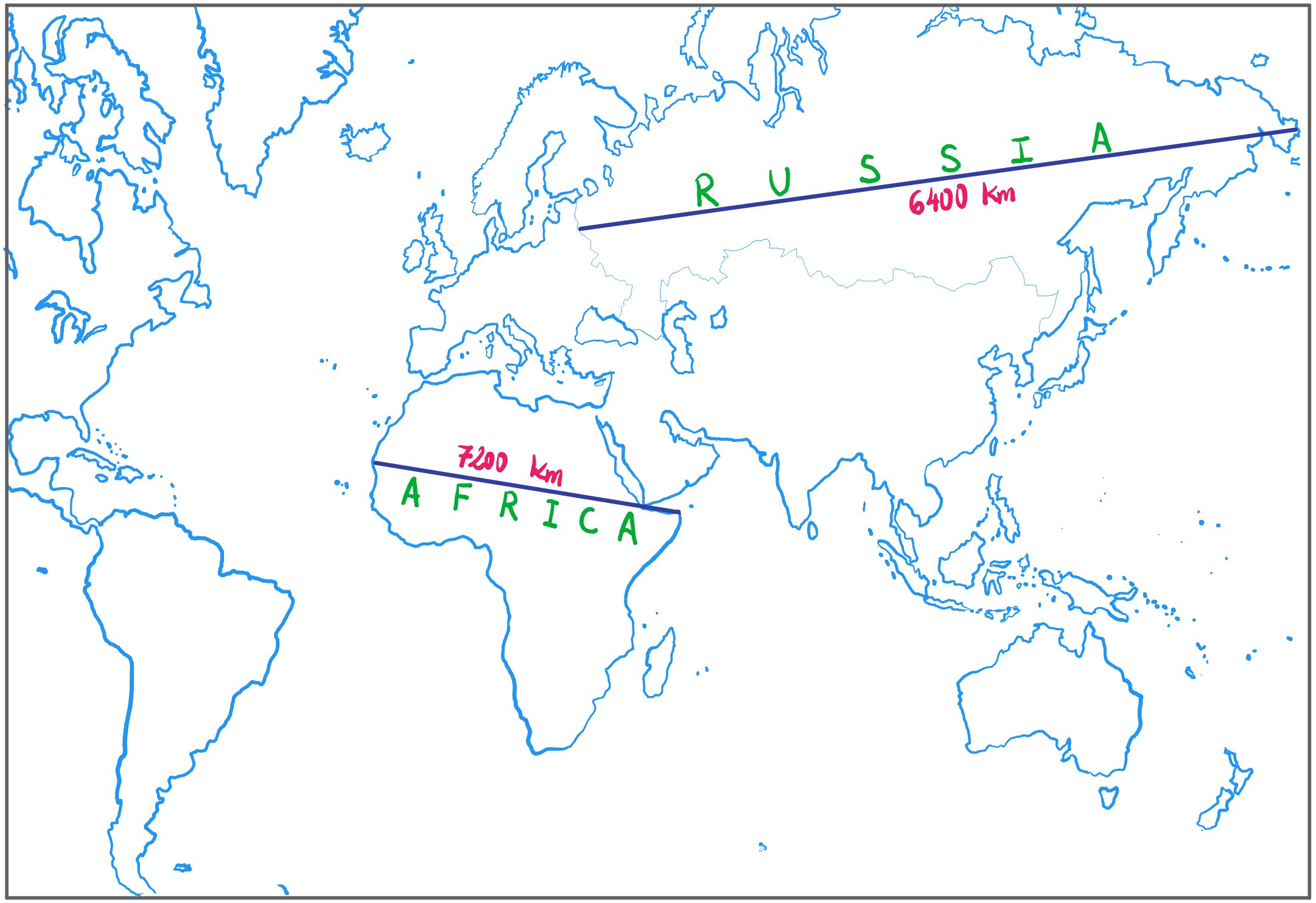

This means that every map—an attempt to give a flat representation of Earth—will be distorted and will not show distances faithfully (see illustration 2) [3].

Illustration 2: A demonstration of distance distortions on maps. On this site [3] you can play with the true size of countries on the world map.

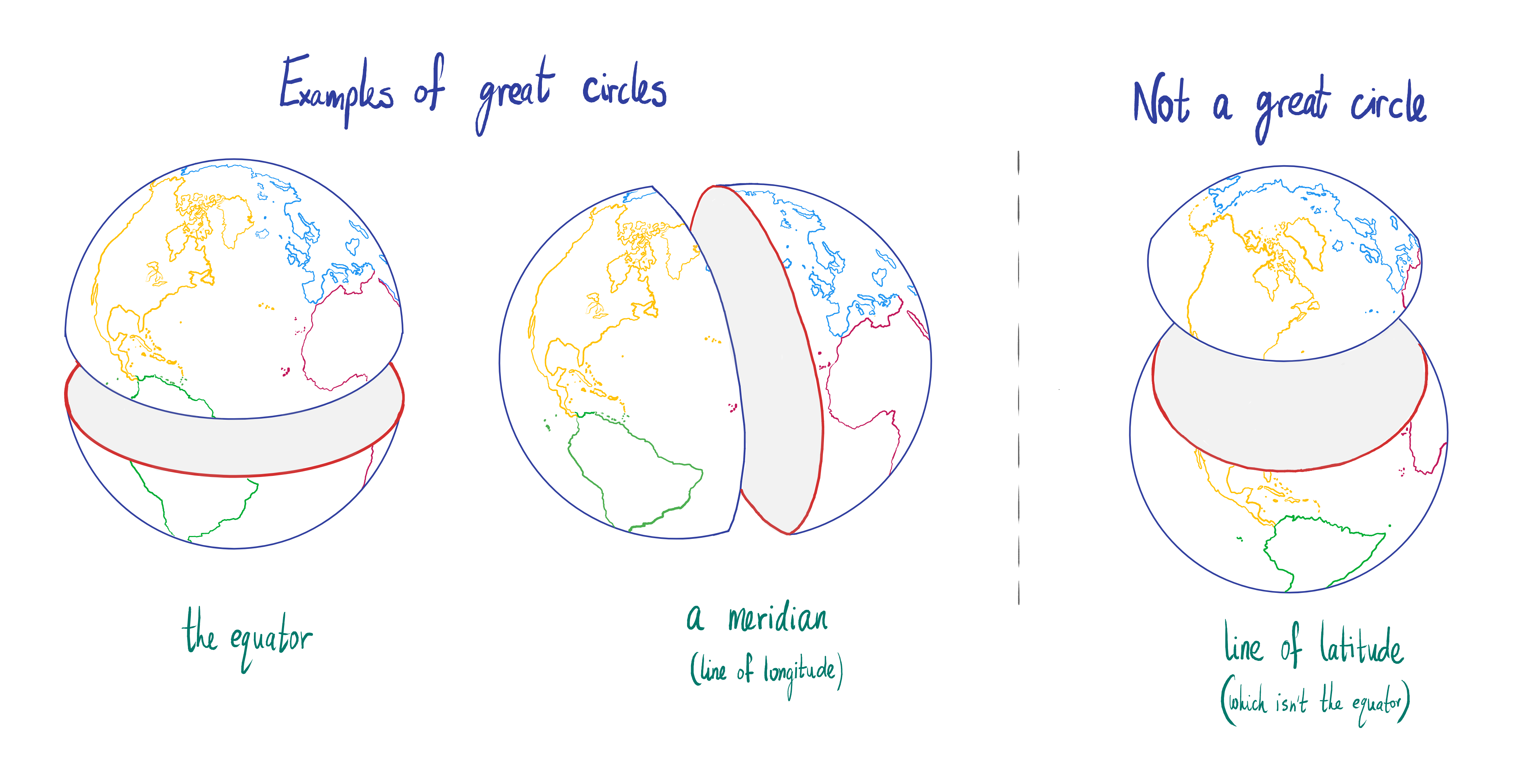

It turns out that on a sphere the shortest path between two points is an arc of a “great circle.” Simply put, a “great circle” is a circle that divides the sphere into two equal halves. For example, every line of longitude is a great circle, and so is the equator. The other lines of latitude, however, are not great circles (see Illustration 3). Through any two points on a sphere one can draw a great circle, and the shortest path between them will be the arc of that great circle passing through them. In this sense, a great circle is the sphere’s generalization of a “straight line”—the shortest path between two points. In any space such a path, whose length is minimal between two points, is called a “geodesic.” As already mentioned, geodesics on a sheet of paper are simply straight lines, and geodesics on a sphere are arcs of great circles.

Illustration 3: Left: a great circle is a circle that divides the sphere into two equal halves. Every line of longitude, as well as the equator, are examples of great circles. Right: a line of latitude (other than the equator) is not a great circle.

Let us now look again at the flight routes from the previous illustration, but this time on the globe (see Illustration 4 below):

Illustration 4. When we looked at the flight route on the map it seemed absurd, but on the globe it is far less surprising: the shortest route from Tel Aviv to Los Angeles really does pass over Greenland (the red path). This path is part of the great circle connecting the origin and destination points. The green path, which looks like a straight line on the map, is not part of a great circle and is therefore longer than the red path. The image was created using this website [4].

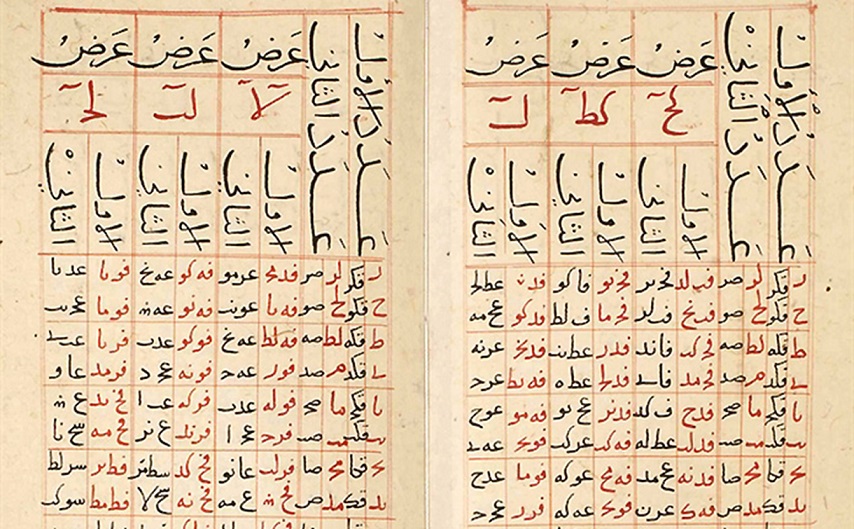

While in Judaism there is no definitive consensus [5], in Islam the preference is for the quick route, and prayers travel along the shortest path, which we have seen is not a straight line on the map but an arc of a great circle. Al-Khalili, a 14th-century scholar in Damascus, produced detailed tables that give the prayer direction according to the worshipper’s location (see picture below).

“The Qibla,” a table of prayer directions by Al-Khalili, Damascus, 14th century. Source: Arabic Wikipedia

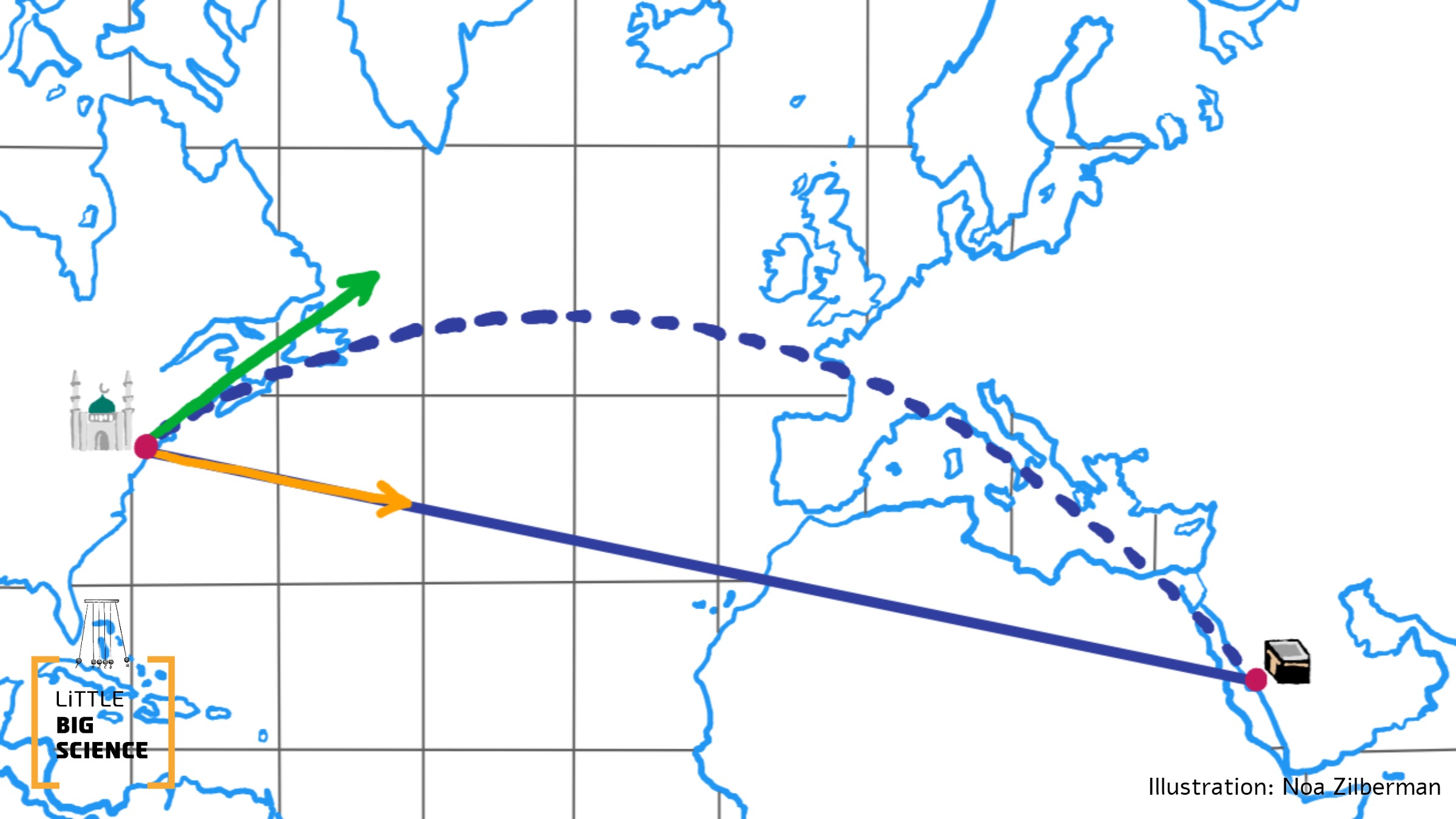

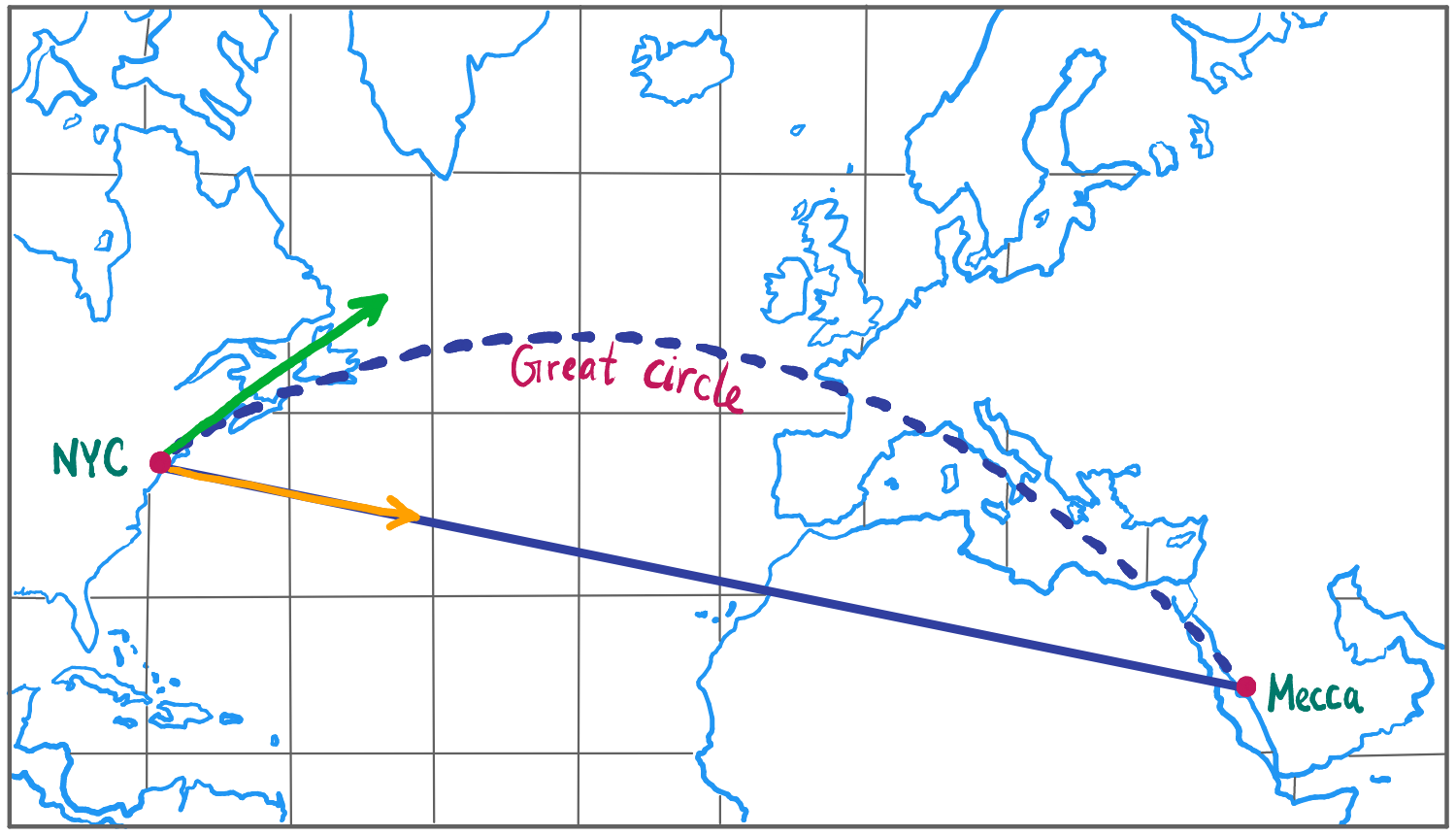

So, although Mecca lies to the southeast of New York, a Muslim in New York will actually pray to the northeast (toward Norway), namely in the direction tangent to the geodesic connecting New York and Mecca (see Illustration 5).

So if on your next flight to New York you fly along a route that looks arced rather than straight, and upon arrival you see a mosque facing northeast, you will know why.

Illustration 5: A Muslim in New York will pray in the direction of the shortest path connecting them with Mecca, namely northeast (green arrow), even though Mecca lies to their southeast (yellow arrow). The dashed line represents part of the great circle connecting New York with Mecca, the shortest path between the two cities. The solid line is simply a straight line on a map, i.e., the line obtained by following a constant compass bearing.

Hebrew editing: Yinon Kachtan

English editing: Elee Shimshoni

References:

- Non-Euclidean geometry and general relativity

- On hyperbolic geometry, another example of non-Euclidean geometry

- The True Size Of…, a site where you can drag countries on the map and see their true size

- Great Circle Mapper, a site where you can plot flight routes on the map and on the globe

- A historical and scientific survey of the directions of prayer in different religions